Eadweard Muybridge: The Photographer Who Froze Time

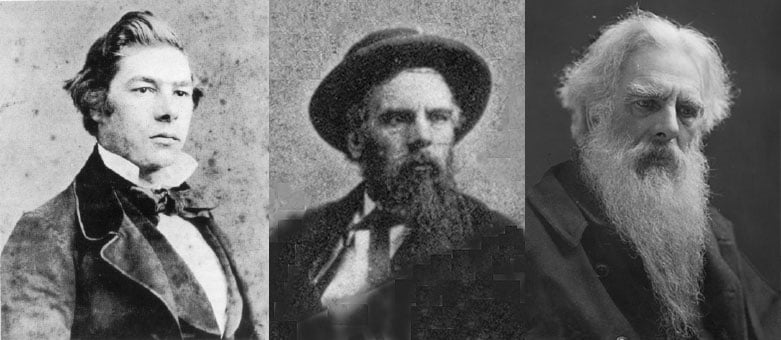

![]()

Before John Logie Baird first demonstrated his television in 1927, before Thomas Edison showed his movie projector in 1888, photographer Eadweard Muybridge was making moving pictures.

Muybridge moved to New York in his twenties and set up a business importing books from England. He soon moved on to his ultimate destination of San Francisco. In San Francisco, he continued his importing business and also began book publishing.

On one trip between California and New York, he was in a serious stagecoach accident. This was a few years before the transcontinental railroad was built, so part of the journey was by slow and dangerous stagecoaches. When the poorly trained team of horses began to run, the driver could not control them and the stage crashed, killing at least one passenger and seriously injuring Muybridge and the others.

Muybridge was unconscious for several days and took months to recover. He later attributed his injuries to causing his hair to turn prematurely gray. His scraggly hair and long bushy white beard caused him to look much older than he was. Many people also attributed the accident to causing a personality change that caused him to act erratically at times. There is some evidence, however, that he was always eccentric and a character by any standards.

A Stormy Start to a Photography Career

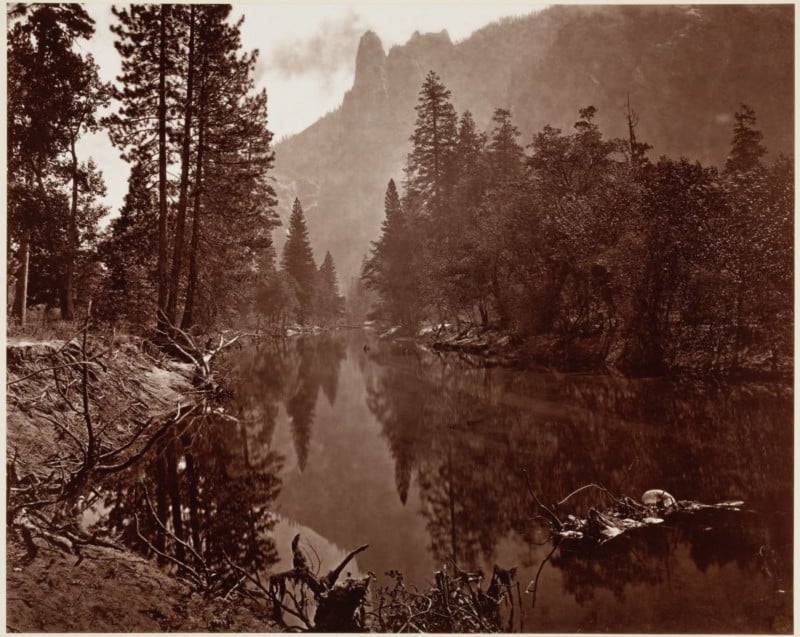

Muybridge became interested in photography through a friend and was soon traveling to Yosemite to make scenic photographs. By all accounts, his scenic photos were outstanding as he was soon making most of his income by selling prints of scenes around Yosemite and Northern California.

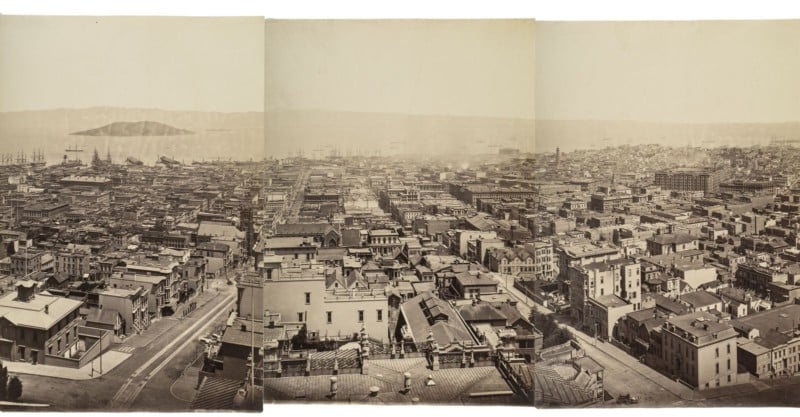

He also made some amazing large panoramic photos of San Francisco.

It was during this time in 1872 that he met Flora Shallcross Stone who was working as a retoucher in a photography studio where Muybridge was affiliated. She was 21 and married while he was 42. She divorced her husband and married Muybridge. Soon after their marriage, she began an affair with a known con man named Harry Larkyns. Flora and Larkyns’ relationship was hardly a secret since Muybridge was away for weeks at a time making photographs.

Flora soon became pregnant with a son. The child’s paternity was never determined for sure, but the midwife, Flora, and Larkyns assumed the baby was Larkyns’s. When Muybridge found out about the affair and that the baby may not be his son, he shot and killed Harry Larkyns on October 17, 1874.

At his trial, the defense attorney used the argument “Not guilty by reason of insanity” and brought in testimony by Muybridge’s friends to prove that he was emotionally unstable. The jury disregarded the insanity defense and acquitted Muybridge on the grounds of “justifiable homicide.” Flora filed for divorce and then died due to typhoid fever five months later. After the trial and Flora’s death, Muybridge made an extended photographic expedition to South America to let things settle and clear his head.

Using Photography to Stop Time

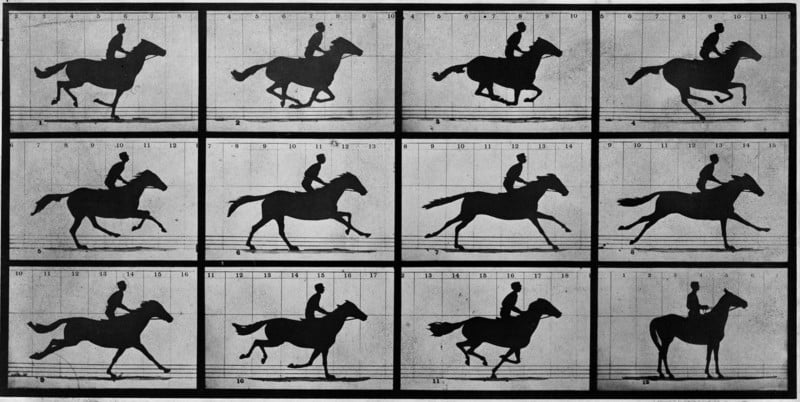

Back in San Francisco, Muybridge’s photography attracted the attention of Leland Stanford, the President of the Pacific Central Railroad and Governor of California. Stanford was a horse aficionado and breeder. He wanted to get photographs of his horses running to determine exactly the moves they were making so he would learn which muscles needed strengthening in order to run faster.

Stanford’s photo challenge was no small task because instantaneous photographs were not possible with the then-current technology. Most exposures were in seconds, not fractions of a second. Cameras did not even have shutters, instead relying on removing the lens cap and counting for the exposure length.

Muybridge accepted the challenge and began the process of finding faster lenses, making faster film emulsions, and designing instantaneous shutters.

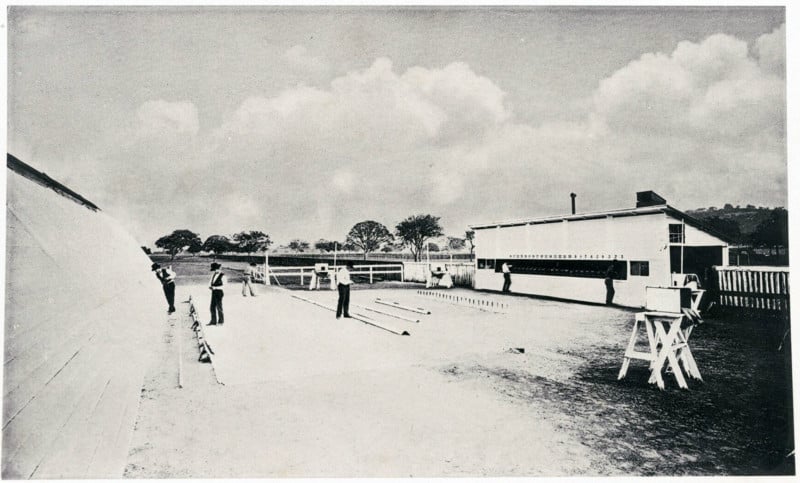

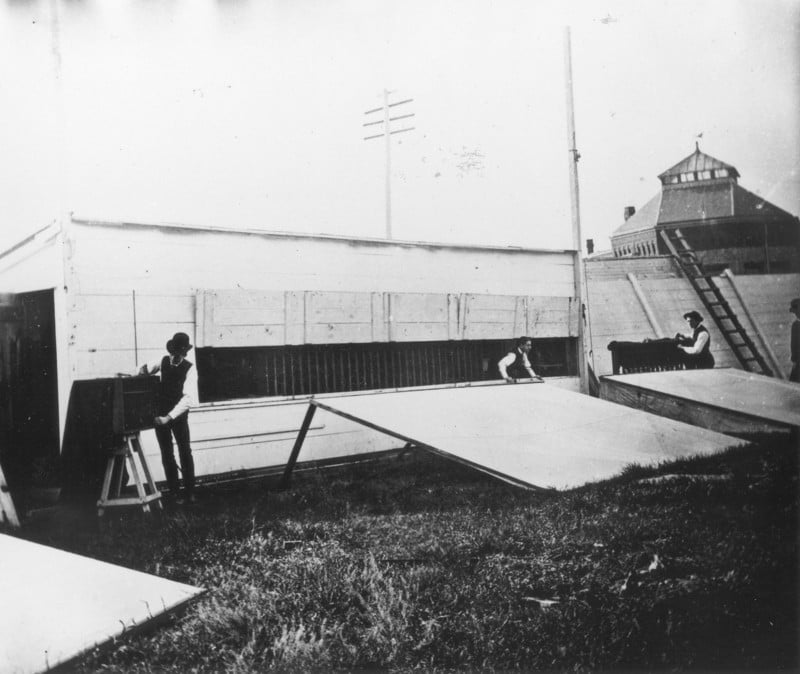

Stanford had bought a piece of property south of San Francisco to build a horse farm that he called Palo Alto Farm. He later established a town there that he called Palo Alto and built a college named after his late son, Leland Stanford Junior University, now commonly known as Stanford University.

Whether Eadweard Muybridge was an employee of Stanford or whether Stanford was Muybridge’s client is not clear and became a serious question later when copyright and credit disputes arose. In all likelihood, Stanford was a client, but Muybridge was not a good enough businessman to get the relationship in writing.

The working relationship was fairly close with Stanford making technical suggestions and providing engineers to help design electromagnetic shutters for the bank of 12 to 24 cameras that were to be fired in sequence as the horse ran by. The photos were made at Palo Alto Farm with Stanford financing the project.

Muybridge spent a good deal of his time traveling and giving lectures about the procedure and amazing audiences with the pictures of horses in motion. While he was in Europe on a lecture tour, Stanford published a book called “The Horse in Motion” without giving any credit or even mentioning Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge was furious, but Stanford apparently believed that Muybridge was just another employee, not worth mentioning.

Paving the Way for Motion Pictures

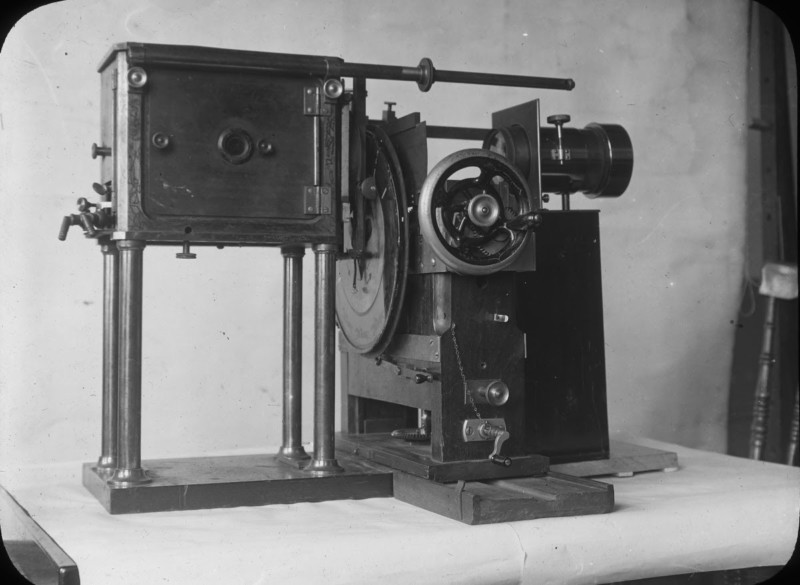

In 1879, Muybridge invented the zoopraxiscope, a device that used a round disc to project sequential images in quick succession. He used it extensively in his travels and lectures, thrilling audiences with the moving pictures.

Muybridge called on Thomas Edison at his shop in New Jersey with the idea of using Edison’s phonograph to synchronize with the images from the zoopraxiscope, but the phonograph was not loud enough to be used in the large lecture halls where Muybridge was speaking and projecting images. It would be a few more decades and electronically amplified sound before sound movies would be a reality.

It was around this time that George Eastman had invented a machine to coat a photographic emulsion on flexible film. This was the link that made the movie camera and movie projector possible.

With Edison aware of Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope, he was likely working on a way to improve it to be used with his own inventions. Thomas Edison quickly patented the movie projector while giving no credit to Muybridge, effectively preventing Muybridge from receiving any credit or income from the invention.

While moving from a spinning disk to a long piece of film was clearly a major improvement, Edison should not get full credit for inventing the movie projector with the historical data known of Muybridge’s earlier work.

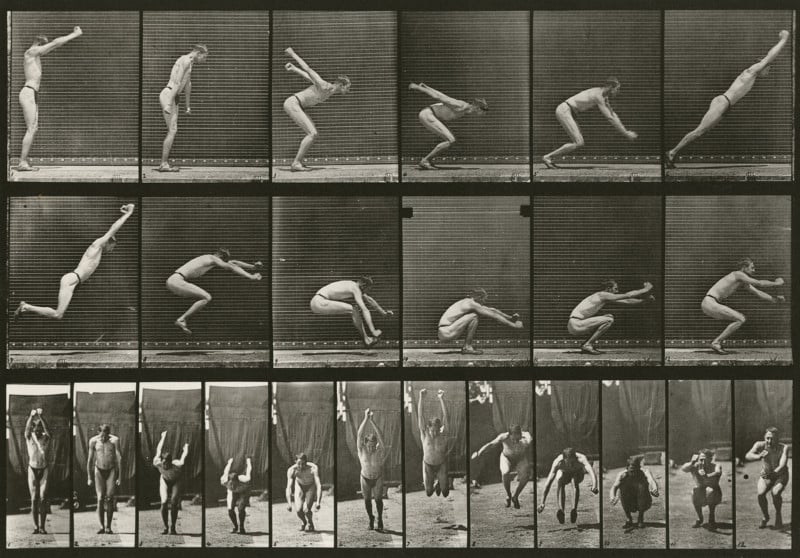

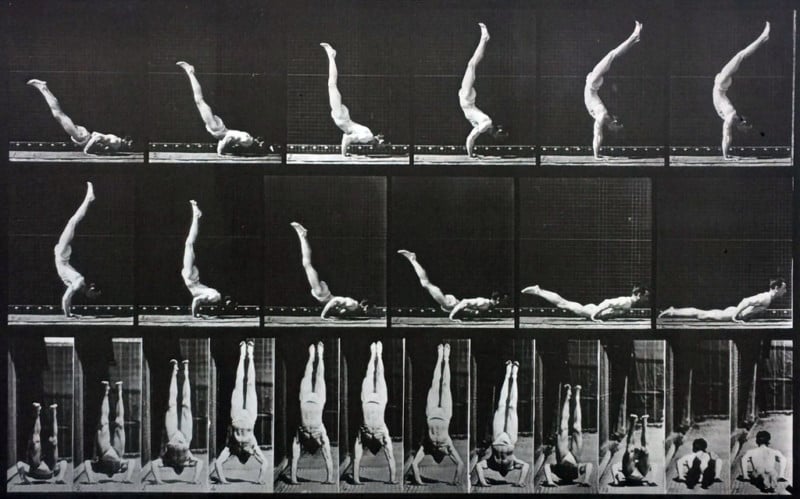

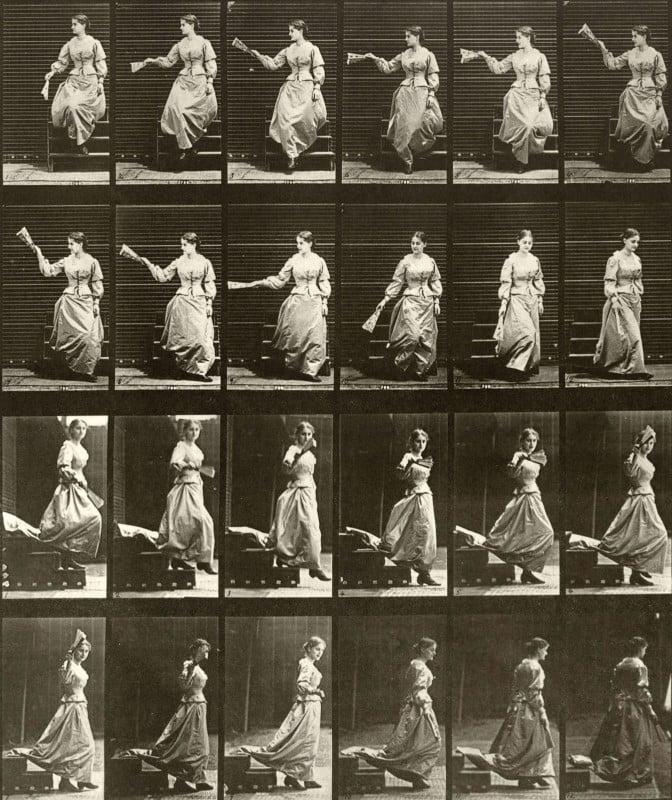

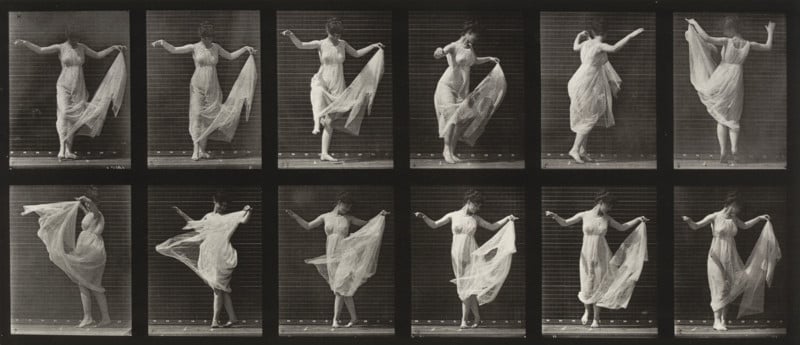

Studies of Human and Animal Motion

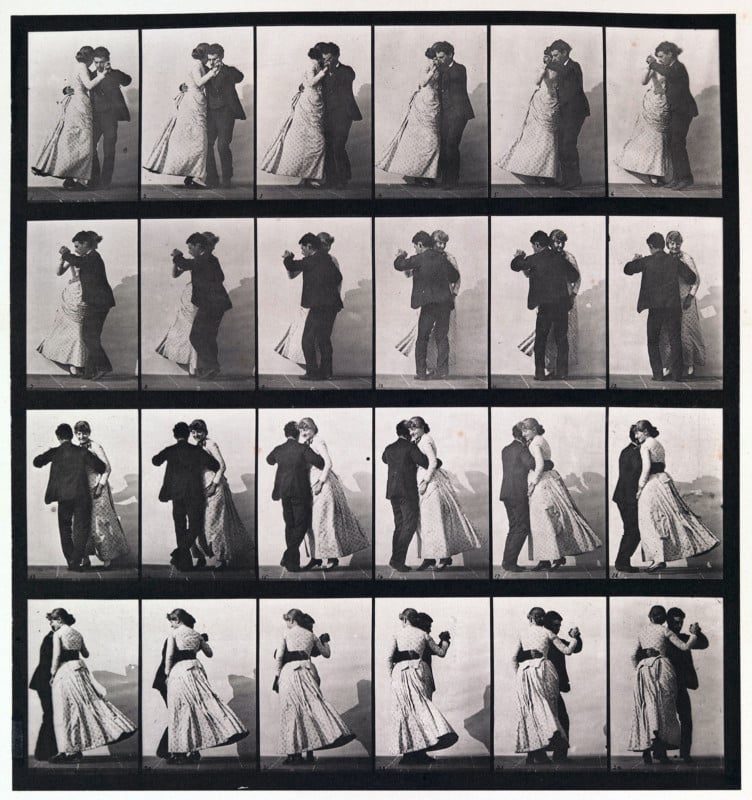

After a long legal battle and lost friendships with Leland Stanford and his previous associates in San Francisco, some of whom testified that he was insane to protect him from the hangman, Muybridge was ready to advance the project with other animals and humans as well. The University of Pennsylvania agreed to an arrangement, basically a research grant, which would allow Muybridge to use university property, some interns as helpers, and art students as models to advance his work.

The university’s interests were primarily research, especially medical, trying to understand how the human body moves and works. Muybridge had already determined that some of the models would have to be nude to show the muscles that were used in various activities. This was, of course, the most controversial part of the project and nearly got the whole project canceled on several occasions. The University of Pennsylvania project took place from 1884 through 1885.

At the Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Muybridge was able to secure space to build a theater to show his moving pictures and sell his books. This was the world’s first purpose-built movie theater. Apparently, the theater was not a financial success because he didn’t renew the six-month lease and sailed back to England in 1894.

Muybridge would make an additional trip across the Atlantic to secure the negatives and prints from the University of Pennsylvania. Once again, there were legal issues over ownership, but eventually Muybridge was on his way back to England with 28 cases comprising more than 33,000 negatives and prints. With these he published Animals in Motion in 1899 and The Human Figure in Motion in 1901. By this time, the half-tone process had been invented and he was thus able to print photographs in books with a conventional printing press. “The Human Figure in Motion” came with a warning which could be summed up as “For Mature Audiences Only.”

Eadweard Muybridge never became a U.S. citizen despite spending forty years of his adult life in California, and he always considered himself an Englishman. He moved back to be close to his family in Kingston, dying there on May 8, 1904, at the age of 74.

He left his zoopraxiscope and the “Animal Locomotion” negatives to the Kingston Borough that now has them on display in the local museum along with a large panoramic print of San Francisco.

For further reading, a great book on the life and impact of Eadweard Muybridge, and a primary source used for this article, is The Man Who Stopped Time by Brian Clegg.