Dorothea Lange: The Photographer of Depression-Era Rural America

![]()

Dorothea Lange was an American documentary photographer who is best known for Migrant Mother, an iconic photo of the Great Depression. Her work helped Americans see the devastating effects of the depression on rural America, and Lange is now celebrated as a pioneer in the field of documentary photography.

After college, Lange and a friend decided that they would travel around the world before they began their careers. They got as far as San Francisco when they were robbed and had to stop and get jobs.

Dorothea took a job at the photofinishing counter of a department store. She had already decided to be a photographer and taking in photofinishing was pretty much an entry-level photography job at the time. She soon got a job as a photographer’s assistant at a portrait studio.

Before long she had her own studio photographing the rich and society of San Francisco. Her studio became the hangout of artists, musicians, writers, and photographers of San Francisco. This community encouraged each other and helped build a desire to help those less fortunate.

Developing a Heart for the Downtrodden

A common idea in the country at the time was that poverty was caused by laziness and that health problems were a result of lack of cleanliness and poverty. As a result, there was very little support for the sick or poor. Dorothea had been stricken with polio as a 7-year-old child and had a long-term partial disability as a result. She had a weak right side and walked with a limp. She knew that bad things can happen to good people and she developed a strong sense of empathy as a result.

One of the artists that hung out at her studio was a western/cowboy painter named Maynard Dixon. They fell in love and were soon married and started a family. But Dixon spent much of his time on the road painting and the couple drifted apart, ending in divorce.

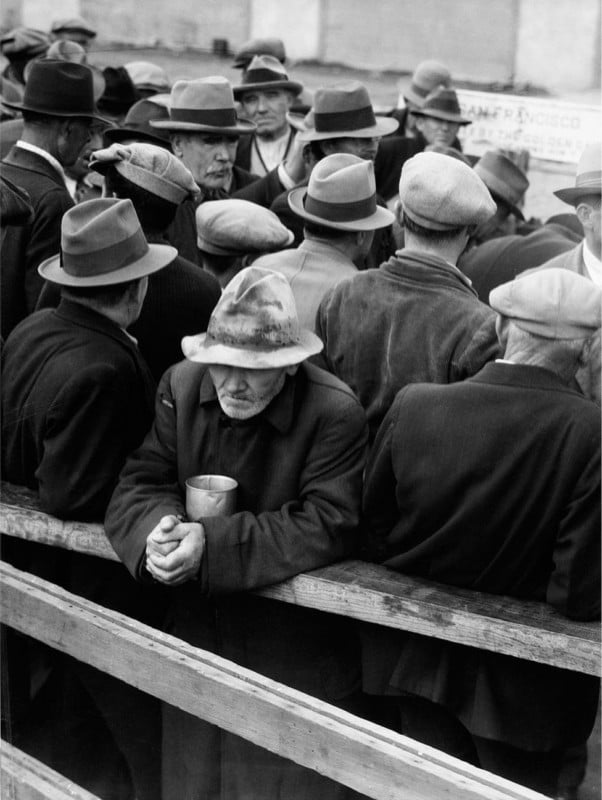

Meanwhile, Dorothea became much more interested in the street people outside her window than the rich people in front of her camera. Her photographs of desperate and homeless people on the streets attracted the attention of a college economics professor named Paul Taylor. Taylor was researching agriculture economics. The plight of American farmers was at an all-time low at this point in the early 1930s.

Paul and Dorothea began traveling together, tied together by a common cause and soon by love, him interviewing migrant farm workers and her photographing them as they went. They got married and began a long and fruitful partnership. Taylor was the opposite of Dixon in just about every way. Dixon was an artist and unreliable, Taylor was a stable college economics professor. Taylor and Lange soon began working for the Farm Security Administration or FSA, the government agency charged with helping distressed farmers.

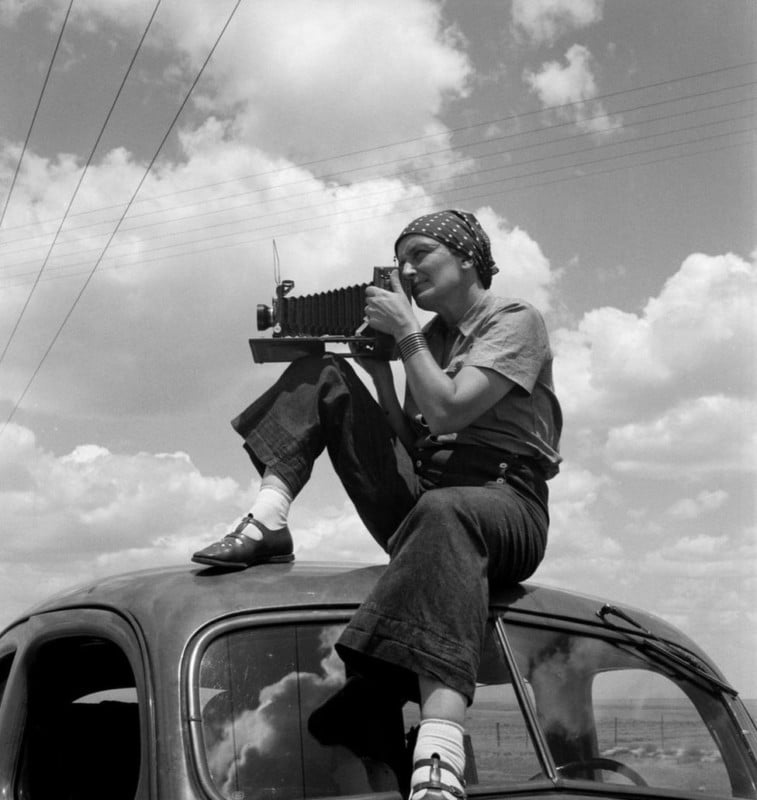

As a professional photographer, Dorothea Lange always used the equipment that she felt was most appropriate for the job. Most of the time this was a large format Graflex Single-lens-reflex.

![]()

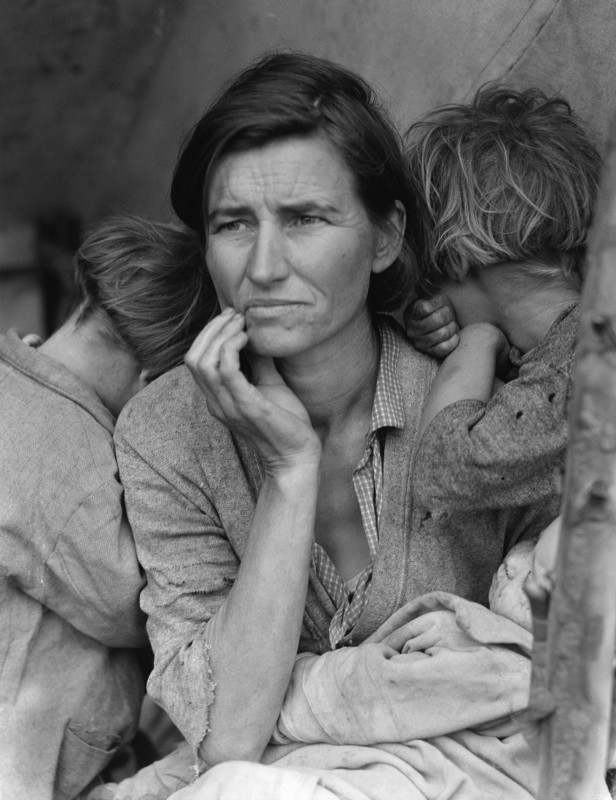

Migrant Mother and Great Depression America

Lange’s most famous photograph was of Florence Owens Thompson in March 1936 in a pea pickers camp near Nipomo, California. The photograph, later titled Migrant Mother, would be published hundreds of times and became the face of the Great Depression for many Americans.

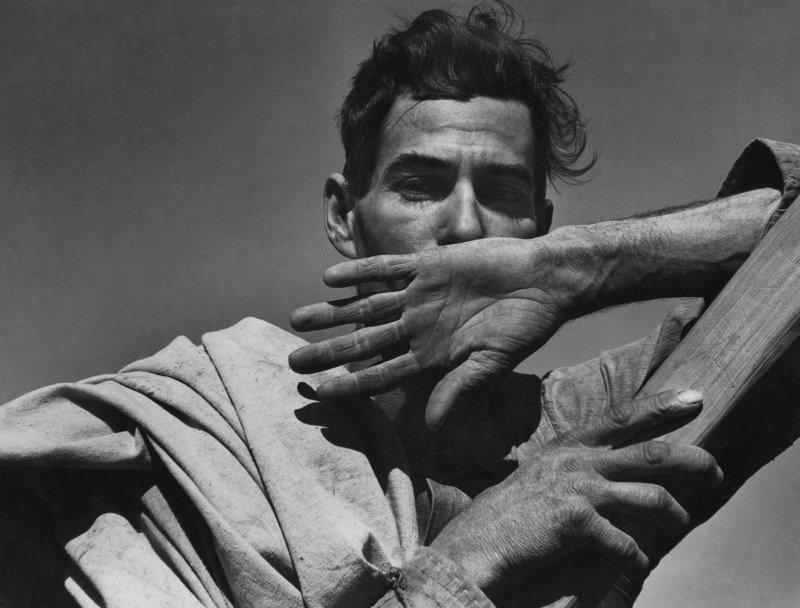

Together they traveled all over the United States, interviewing all sorts of people in desperate situations. Her photographs were published in newspapers and magazines as the public began to see firsthand the horrors that the Great Depression had inflicted on a great number of people.

Dorothea Lange’s photographs along with other FSA photographers made a huge impact on the political climate and were very instrumental in building public support for President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs.

Public jobs programs such as the WPA (Works Progress Administration) as well as relief programs were approved as people could see firsthand through photographs the devastation of lives caused by climate and economic conditions that were in no way the fault of those suffering the most.

Because of this attitude change we now have Social Security, unemployment insurance, welfare programs, and many other safety net programs that have prevented a major disaster such as the Great Depression from happening again.

Just as we have photographers like William Henry Jackson to thank for our National Parks, we can thank Dorothea Lange and the other FSA photographers for our economic safety nets and government programs that help protect the health and well-being of us all.

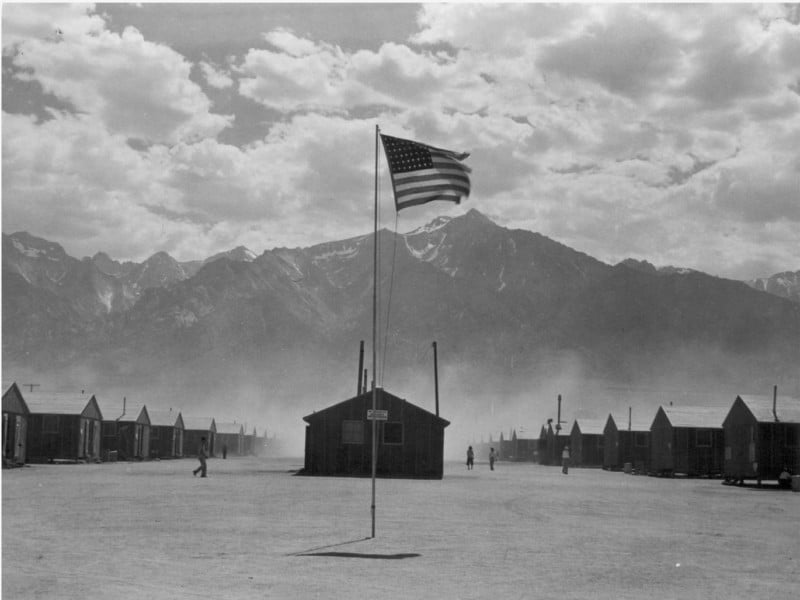

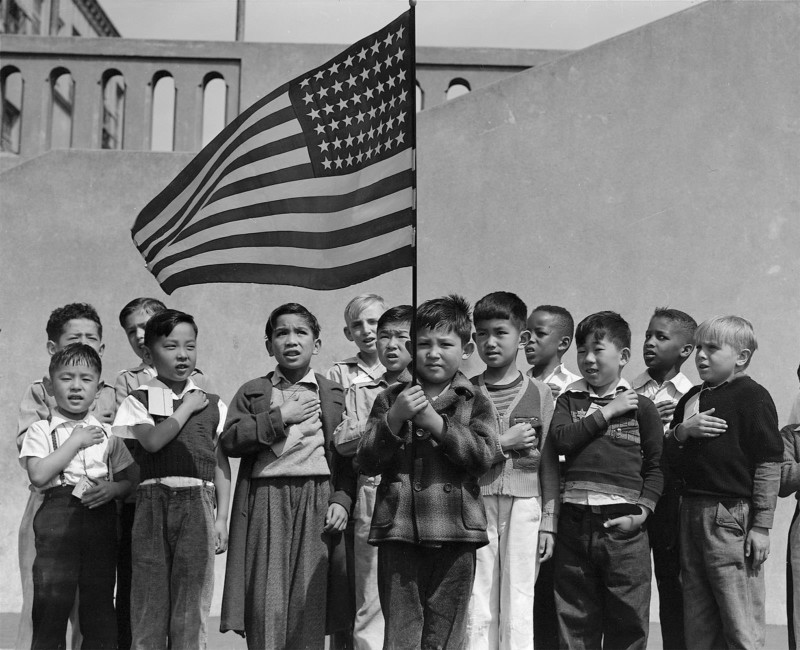

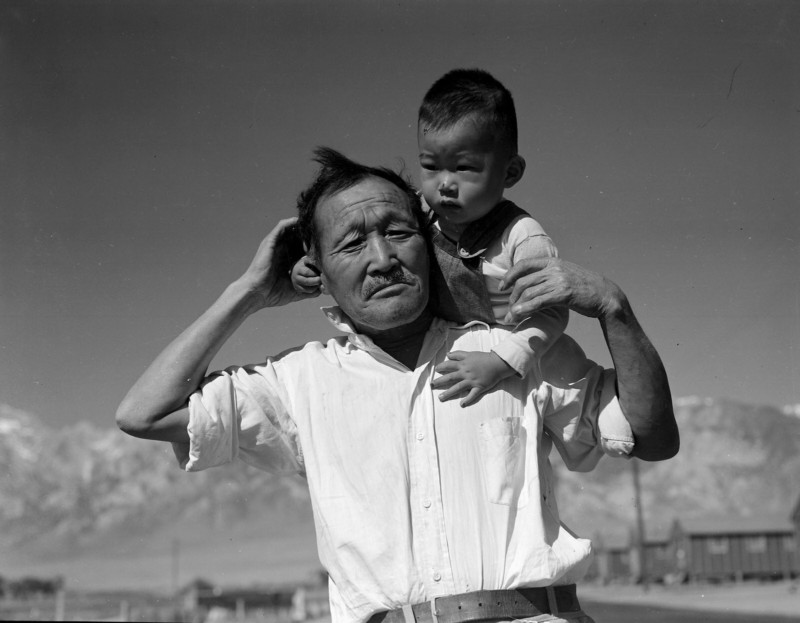

Japanese Internment Camps

During World War II, Lange was hired to document the Japanese Internment Camps where U.S. citizens of Japanese descent were imprisoned during the war. It was many years before these images were declassified so that we could see the inhumanity imposed on our own citizens by the government because of the unmerited fear of immigrants, especially during wartime.

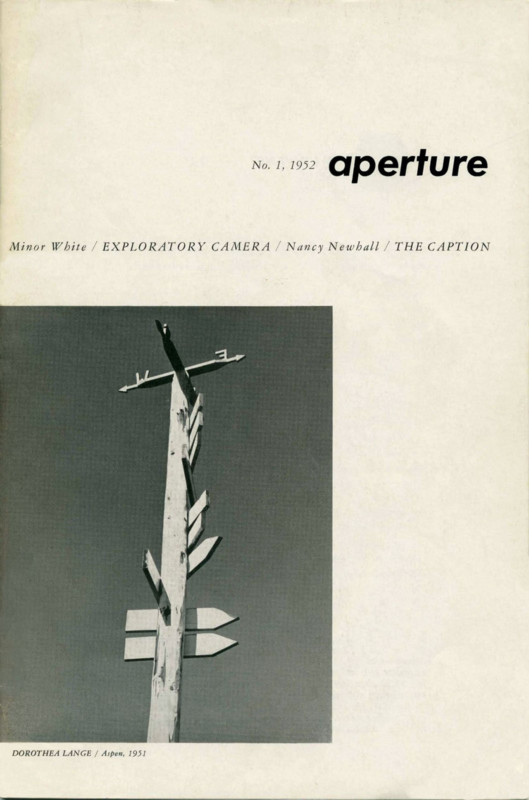

A Cofounder of Aperture Magazine

After the war, Paul and Dorothea spent the rest of their lives traveling, writing, and photographing the less fortunate. Their photographs and stories were often published in major magazines such as Life as well as the magazine she co-founded, Aperture.

Created in 1952, Aperture set out to be “common ground for the advancement of photography,” Aperture today is a multi-platform publisher and center for the photo community. From the base in New York, they continue to produce, publish, and present a program of photography projects, locally and internationally. This magazine offers a quarterly magazine, photobooks, touring exhibits, and other important contributions to the photographic community.

Because of Dorothea Lange’s influence and career, she became the first woman awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1940. In 1945 she joined the photography faculty of the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) along with other outstanding photographers of the day including Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Minor White, Edward Weston, and Lisette Model.

Dorothea Lange died in 1965 at the age of 70. She was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame in 1984.