A Brief History of Olympus, From the Six to OM Digital

![]()

Throughout the history of photography, few names have endured for as long and few have left as significant of an impact on the medium as Olympus.

Before the Six: The Beginnings of Olympus

Founded in 1919, the Olympus Corporation was one of the first in a series of emerging optical companies sprouting from Japanese soil. A few, like Minolta, came before, but none would last as long in the photography industry as Olympus.

Except, for the first few decades of its existence, Olympus never really thought much of designing cameras. It didn’t even bear its now-iconic name at first!

Founded as K.K. Takachiho Seisakusho, the company only began using the Olympus moniker for one of its best-selling products of the 1920s. No, not a camera – a microscope, actually!

In its youth, Olympus specialized in optical designs for the medical industry. It actually established an enduring reputation in this field, which even in years of struggling photographic sales helped keep the business afloat.

Olympus also diversified into other areas during this time, such as ophthalmic lenses for prescription glasses.

Dipping One Toe Into Photography: The Semi-Olympus

In the 1930s, Olympus took one daring step that would end up defining the brand for generations to come. With its reputation as an excellent medical and ophthalmic glassmaker firmly established, the company chose to try its hand at a photographic lens, too.

Cameras at that time were not very common or cheap in Japan, and the vast majority of what was available was either imported or built in Japan based on foreign blueprints.

By contrast, the Semi-Olympus, as it was called, was essentially an Olympus lens – bearing the iconic Zuiko name – attached to a body designed and produced by a different Japanese company, Proud.

To name their first offering a Semi-Olympus might sound strange to our ears today, but back in 1936 when it was released, the moniker made sense. The Semi-Olympus shot 6×4.5cm negatives on 120 film, a format that has faced a lot of neglect throughout photographic history but actually enjoyed a lot of popularity in Japan during the decades surrounding World War Two.

Because a 6×4.5 negative covers exactly half of the frame of a standard 6x9cm image, the “half-frame” medium format was referred to as “semi film” in Japan back then. Hence, the Semi-Olympus.

Upon its release, the Semi was expensive, aesthetically hard to tell apart from the competition, and made by hand in small batches, all contributing to low sales.

However, from the standpoint of an already financially healthy corporation such as Olympus during the late 30s, it fulfilled its goal: what little reviews of its performance were published, they all highlighted the strengths of that Zuiko 75mm f/4.5 lens.

And that was exactly what Olympus had been looking to achieve.

Expanding the Photography Business

Following up on the little Semi, Olympus decided to develop a slew of camera models in-house, without the assistance of Proud.

The Semi-Olympus II was an updated design with an Olympus-made body that featured a better fit and finish, a more ergonomic viewfinder, and various other small improvements. Like the original Semi, however, the Semi II was mainly made as a vehicle to popularize the impressive optical craftsmanship behind those Zuiko lenses.

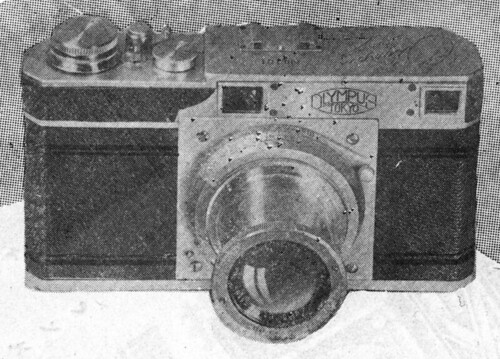

While sales continued to be rather modest, they were an improvement over the original. To diversify their portfolio, Olympus added the Standard, a small rangefinder camera that, despite its Leica-esque appearance, shot 5x4cm negatives on 127 film.

With its more complex high-speed, focal-plane shutter and fast lenses, not to mention the added cost of a coupled rangefinder, the Standard unfortunately proved too much of a risk for the still-rising company. After a short run of ten prototypes, it never entered serial production.

The Olympus Six, A Breakout Hit

The first Olympus camera that would really manage to capture a significant share of the market, both at home and abroad, was the Olympus Six.

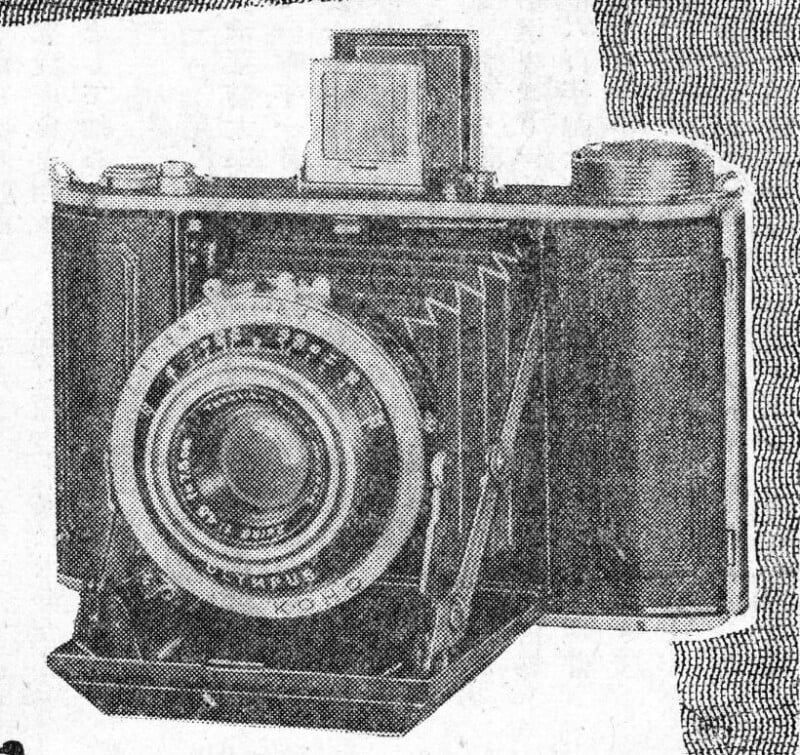

Initially, it was introduced in the year 1940 as a reworked version of the Semi II with the ability to shoot square, 6x6cm negatives. It received few updates through the 40s, mostly owing to the harsh conditions of wartime Japan’s economy.

With the end of the war, however, big changes were in store for Olympus. First of all, the company officially adopted its famous name – all of its pre-war cameras might have borne the “Olympus” name on their bodies and lenses, but the company itself didn’t legally let go of the old Takachiho title until 1949, becoming Olympus Optical Co., Ltd.

In the year 1948, Olympus decided to revamp its existing camera model and add a “little sister” to fill the role previously assigned to the failed Standard.

The Six changed all throughout that year. The body was refashioned in high-end chrome, with lots of small ornamental touches and precise fittings. Its viewfinder now corrected for parallax, and a more refined, faster lens was fitted.

But the real star of ‘48 was the Olympus 35. This small-scale focus camera took tiny images on then-novel 35mm film – the first Japanese camera with a leaf shutter ever designed and sold for the format. The Olympus 35 actually took pictures in the size of 24x32mm, not 24×36 as is now common.

The former survived for a few years after the end of the war as “Nippon format” or “Japanese 35” until almost all Japanese camera makers, including Olympus, ended up switching to the worldwide standard by the year 1952.

With many iterative changes, the 35 and the Six would end up becoming Olympus’ first runaway successes. Gaining in complexity, build quality, and especially optical construction as the years went by, both of these models set the stage for Olympus and its evolving identity as a brand.

Enter Yoshihisa Maitani: Olympus’s Golden Era

Olympus clearly established itself as a force to be reckoned with during the early postwar years in Japan.

While sales abroad were nothing to write home about just yet, local reviewers and the few American photographers that got hold of Sixes and 35s during this time only had good things to say about the build quality and the images those Zuiko lenses were capable of producing.

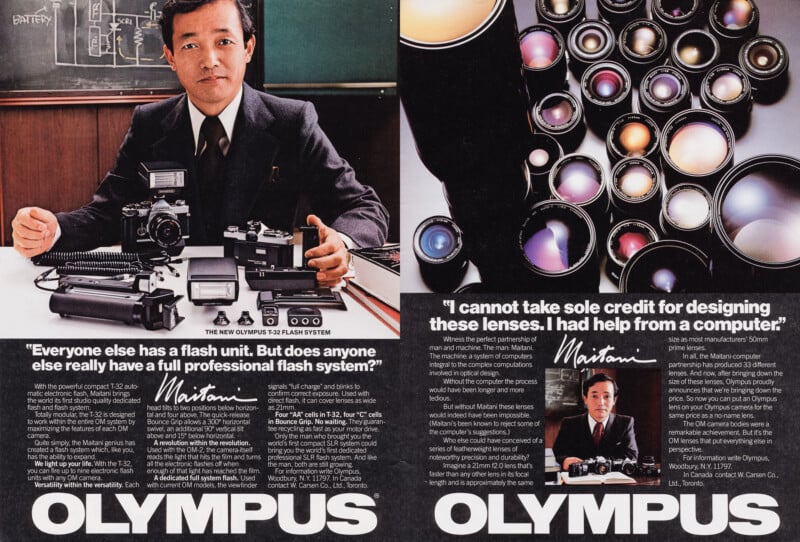

A follow-up had to come to really ride the wave of that success and turn it into something huge. That follow-up came not in the form of a blueprint, a patent, or even a prototype at first. Rather, it came in the form of a new hire, a young man by the name of Yoshihisa Maitani.

The son of a sake maker, Yoshihisa had a lifelong passion for photography. He loved going out on long photo walks with his favorite Leica IIIf, a camera he adored – though he found flaws with it, such as the rangefinder’s limitations when attempting close-up photography.

In his free time, first as a teenager and then later as an adult, he tinkered and tinkered with plans for a design of his own camera that would improve on what he saw as the Leica’s inherent shortcomings.

Yoshihisa only ever intended for this design to be something he would try and assemble himself in his shed for his personal use. He went to university at Waseda, a rather prestigious institution in Japan at the time, with plans to go into automotive engineering instead.

That is, until one day in 1956, when one of his lecturers, who happened to be the then-lead designer of Olympus cameras, caught wind of Yoshihisa’s blueprints and expressed the company’s interest in producing them.

The Making of the Olympus Pen

Maitani’s first camera would end up becoming Olympus’ most significant project yet, and a huge undertaking for a company that hadn’t yet spent more than a few decades firmly in the photography business.

Despite his young age and complete lack of working experience, the top brass at Olympus gave Maitani a huge amount of creative freedom and afforded him a generous budget.

Operating under the mindset that a camera’s body serves a purely aesthetic purpose and should be secondary to its optics, young Maitani blew the whole budget allotted to his project on designing the D-Zuiko 28mm f/3.5, a fantastic and highly compact wide-angle lens.

This nearly doomed the whole project, but after much internal debate, Olympus gave Maitani a conditional go-ahead.

He could finish his work on the camera, but only if he could present something that could be sold for less than 6,000 yen. In today’s money, that is less than $150, and about a third of what the cheapest version of the Six cost!

The result was something he called the Olympus Pen. The name was the first in the company’s history not to refer to the camera’s film format, despite the fact that it shot images in an aspect Olympus had never tried before – half-frame 135-format, 18x24mm.

This was chosen for two reasons: one, high film prices in Japan at the time meant that half-frame cameras were a serious value proposition, hammering out up to 72 exposures on a 36-exposure roll! And two, Maitani was a devout cinephile and saw great aesthetic value in the half-frame format’s proportions, which are identical to a shot of 35mm cinema film.

The “Pen” nickname came from the camera’s diminutive proportions. Maitani wanted his first camera to fit inside the breast pocket of a button-down shirt, where engineers often kept their pens.

Beyond all expectations, the Olympus Pen sold like hotcakes. Whereas previous sales of Olympus cameras had been measured in the hundreds, growing into the thousands each year during the 1950s, the Pen shipped a whopping 15 million units between the 60s and the year 1981, when it was discontinued as one of the brand’s longest-running model lines ever.

The Pen F Family

The immense success of the original Pen and its many variants designed by Yoshihisa Maitani gave him a highly respected position within the company hierarchy of Olympus.

It was not very long before he was given the budget and the resources to build the camera he had always wanted to make since his youth: a “modernized Leica” with a whole system of interchangeable lenses and macro photography capabilities.

Early on during the design process, he figured out how he would solve the problem of close-up focusing while maintaining extremely small, Leica-like proportions at the same time.

That is, by making the new Olympus Pen an SLR, but with its reflex mirror shrunk in size and inverted, using a series of small prisms to direct light through the body. This completely nullified the need for a large pentaprism hump sticking out from the body.

To further drive down dimensions and to convey a family resemblance, the new Pen F (F for “reFlex”, like the Nikon F) would also shoot half-frame exposures on standard 35mm film cassettes.

Maitani also gave the camera a unique front-mounted shutter speed dial. This was not only to free up the top plate from potential clutter but to evoke a pastiche of the Leica IIIf, which had its slow speed dial in the same position.

The shutter, too, was one of a kind. Maitani wanted the new Pen to have an in-body shutter that would be capable of firing at high speeds, synchronize with flash at every setting, and that could be as quiet as that of his dear Leica IIIf.

At the time, such a thing was thought impossible, an engineering puzzle that nobody could solve.

It took a whole team of geniuses and a lot of funds, but in the end, Maitani and his colleagues came up with a custom metal-bladed rotary shutter, similar to the kind used in movie cameras.

Upon release in 1963, the Pen F came with a lot of hype attached, and initial sales were strong. Reviews also praised the camera for its build quality, the highly unique design, and the excellent optics from its lens lineup.

Famously, Ponder & Best ran a marketing campaign that featured W. Eugene Smith (yes, the Eugene Smith) displaying a whole Pen F system, including lenses and lots of accessories, tucked into his shoe.

But the magic wouldn’t catch on. Despite lots of praise and widespread cultural recognition, the Pen F didn’t manage to ignite the industry-wide shift towards the half-frame format that Maitani had hoped for.

Journalists and reporters especially, save for exceptions like Smith, preferred to stick with full-frame or even larger formats like 120 and 4×5 sheet film for their large prints.

While the consumer-oriented Pen series would live on and become a great success, the Pen F only stuck around for the remainder of the decade before being quietly put to rest.

Olympus Conquers the World With the OM

Obviously, this sent a message to the camera design team at Olympus. Half-frame 35mm, for all its virtues, just couldn’t conquer the photography market where it was really crucial: at the upper midrange and the high end.

So, doing what he knew best, Maitani went back to the drawing board to design a full-frame 35mm SLR that would do as much as what the Pen F had done as possible, yet yield larger negatives.

The result? A name so legendary it became permanently associated with Olympus itself – the OM-1.

July 1972.

In its silhouette, the OM was a lot more of a traditional SLR, looking not too far off from a contemporary Pentax or Nikon. But put the three next to each other, and something amazing happens.

While it’s no big surprise that a contemporary Nikon F or F2 will absolutely swallow a Pentax Spotmatic, the OM manages to look tiny next to both of them. Called the most compact and pocketable full-frame SLR in the world upon its release, it still just about manages to take the crown, at least depending on whom you ask.

Armed with a sharp match-needle exposure meter, the Olympus OM-1 became the company’s best-selling camera yet. It defined the look, feel, and function of cameras for the 70s. Small, pocketable, and stylish SLRs were now the prestige item to beat.

The OM line ended up growing and maintained incredibly competitive sales throughout the decade and beyond. Its “double-digit” models, like the OM-30, pioneered many of the electronic aides and automatic features that would distinguish cameras in the 80s.

During these two decades, Olympus enjoyed a position at the top of the photography business. It appeared that all the other brands, at least in some sense and for some time, were playing catch-up to the ideas Olympus was generating.

Maitani’s Most Daring Take, the Olympus XA

Riding high on the waves of superstar-level success, Maitani would, towards the end of the 70s, design one more monumental camera that would showcase the culmination of his personal philosophy, no expenses spared.

That culmination was the Olympus XA. A tiny, almost unbelievably small 35mm rangefinder camera made out of black ABS plastic, it was positioned as one of the most affordable Olympus cameras in the company’s lineup. Its most distinctive feature is the sliding action of its outer body, which simultaneously covers and uncovers the lens and viewfinder for protection while also acting as an on-off switch for the meter.

The XA set many records. It became the smallest 35mm camera taking full-frame exposures ever made, and one of the smallest rangefinder cameras ever made overall.

Today, it’s a design icon and a valued collectible that can fetch high prices – sometimes far higher than originally more upmarket designs such as the Pen FT or the OM-3.

Entering the Digital World Boldly

The 80s and 90s were an era of smooth sailing for Olympus. With the help of trailblazers like Maitani, the brand had managed to climb to the top of the industry hierarchy and become a leader in every sense.

Its OM series and various compact cameras like the XA and its many variants continued to sell well even as the millennium drew to a close.

However, Olympus was not blind. The top brass at the company was well aware of the digital revolution that would soon take place, and they heavily invested to be able to confront it gracefully.

This resulted, in a sense, in the creation of an entirely new Olympus – one that would enchant a new generation of photographers, forging an identity that took inspiration from the past to sail towards the future.

From Four Thirds to Micro Four Thirds

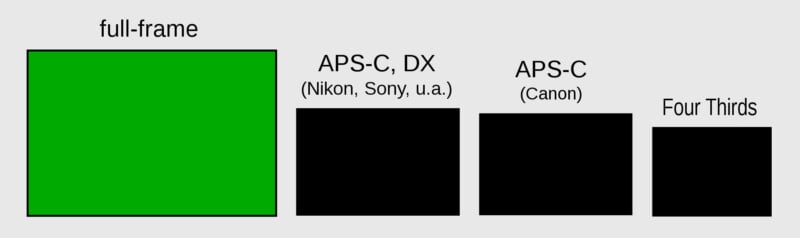

The first great achievement of Olympus in the digital era was pioneering the 4/3 system, officially spelled out as “Four Thirds”. Until the late 2000s, all consumer-grade digital cameras from other manufacturers used crop sensors matching the failed APS film format in terms of dimensions.

In other words, they shot pictures much smaller than 35mm film negatives.

Olympus chose to exploit this by pioneering their very own sensor format. Made with the help of Kodak (which was still invested in digital camera research and development at the time), the idea behind the Four Thirds system was to create a sensor that would have a crop factor of 2.0.

That is to say, images shot on Four Thirds would present the same field of view as images shot on 35mm film with a lens of twice the focal length. Compared to that, the crop factor of APS-C sensors is 1.5.

The Four Thirds standard went beyond sensor size: designed to be “open”, Olympus actively encouraged other manufacturers to chip in with lens designs, aiming to create an entire Four Thirds ecosystem that would be all inter-compatible.

When full-frame digital cameras did arrive, spelling doom for smaller sensors, Olympus chose to actually double down on its philosophy instead of backing away from it.

They went ahead and introduced Micro Four Thirds in the year 2008, this time with the help of Panasonic following Kodak’s demise. Micro Four Thirds features the same sensor dimensions as its predecessor, but it removes the optical viewfinder.

The idea behind that choice was to streamline the design, making it easier to manufacture and opening it up to more third-party lens makers. Because Micro Four Thirds cameras have no swinging mirror to account for, producing lenses for them is much easier.

The lens mount on a Micro Four Thirds camera is smaller and has a shorter flange distance — the distance between the sensor and the lens mount — compared to Four Thirds cameras. This smaller lens mount design allows for cameras that are much lighter and smaller than any that came before – not just compared to the old Four Thirds cameras, but compared to just about any enthusiast-grade digital camera available at the time!

To look back on this now and think that Olympus was committing to the mirrorless revolution as early as 2008 is mind-boggling, to say the least.

A PEN With a New Face

The first of Olympus’ Micro Four Thirds cameras would bear a familiar name: Pen!

Though not designed with Yoshihisa Maitani’s involvement, the new Pen E-P1 pays homage to the originals in a variety of ways.

Following them closely in terms of dimensions (impressive for a digital camera) and likewise equipped with stellar Zuiko lenses, the new digital Pens won praise from the press and quickly became Olympus’ best-selling digital cameras.

A higher-priced PEN-F, a clear throwback to the Pen SLR of the 60s, did not sell as well, but its ambitious design and retro controls also found many fans.

Throughout the rest of the 2000s and 2010s, Olympus’ digital Pen line would define the brand’s aesthetic for the masses: chic, super-compact, yet high-quality and sporting world-class optics.

The OM Gets a Facelift, Too

With the OM-D line, a separate series of digital Micro Four Thirds cameras that clearly gets its looks from the handsome OMs of the 70s and 80s, Olympus even managed to recover some of the dominance it had had in the higher end of the camera market.

Chiefly marketed towards wildlife, action, and outdoors photographers, the OM-Ds use the same lenses as most of the digital Pens, yet they employ tougher construction with weather-sealing and other improvements.

As before in the 60s with the Pen F, many professional photographers expressed concerns over the small sensor size of the OM-D cameras. In the end, they still found success, not in the least because of their excellent build quality and their high crop factor, which allowed the use of unusually small and light, hand-held telephoto lenses.

The End of Olympus?

In June of 2020, startling news broke. After almost a century, Olympus made the decision to quit the camera business and focus entirely on other ventures.

The camera and optics division of the company, so it was announced, would be spun off and sold to a quasi-independent subsidiary under the name OM Digital Solutions.

Olympus cited the complete evaporation of the low and mid-end digital camera market due to the smartphone revolution. Because the OM-D line was never close to matching the sales figures of Nikon or Canon despite undercutting them in price, it could not manage to sustain the company all by itself.

Initially, not much changed. OM Digital kept the existing Olympus lineup in production with basically no alterations. However, they soon announced that a new camera bearing the OM System name would make an appearance.

Called the OM-1 and released on the 50th anniversary of the original OM-1 in 2022, the camera was far more than a little throwback to good old times. With its rugged, weather-sealed, and stabilized body, advanced computational photography features, a stacked sensor, and a price tag clearly meant to throw some shade at the leaders of the camera market, the OM-1 landed with a bang.

The OM-1 would still feature the “Olympus” nameplate on the viewfinder hump, but that too would go with the follow-up model, the OM-5.

At the time of this writing, it’s still uncertain where OM Digital will take Olympus’ legacy. But judging by how they have taken the reins, I don’t think we’ll need to worry too much. After all, it would take a lot to sully a reputation built on over 100 years of making some of the best optics in the world.