A Brief History of Color Photography

![]()

When photographing the world around us, the property of color is likely something most people tend to take for granted. We expect our cameras to portray the visible light spectrum accurately. However, in a world so engrossed with color, we sometimes forget how long it took to get to this point in time and how many photographers and scientists viewed the concept of color photography as a pipe dream.

As soon as we realized that it was possible to capture light with our cameras, we wanted to harness all the colors associated with it. Some of the first experiments began in the mid-19th century. The original approach was to find a material that could directly share the color properties of the light that fell upon it.

The ‘Hillotype’ Process by Levi Hill c.1850

The ability to capture color came in 1851 from a minister living in upstate New York.

Levi Hill was a Baptist minister living in the New York Catskill Mountains area. He previously used the daguerreotype process to capture photos but was disappointed in its lack of ability to reproduce color. Many were skeptical when Hill announced he had found a “Hillotype” photographic process to make it possible.

Hill refused to release his secret process until 1856, when it was published in a book only available by preorder. When photographers finally got their hands on the book, they found that it did in fact contain a recipe for the process, but it was so complicated that it was regarded as useless.

Interestingly enough, over a hundred years later in 2007, researchers at the National Museum of American History were able to analyze Hill’s work and found that he did figure out a way to reproduce color. They found that the process was very muted, and pigments had been used to enhance some of the colors. While Levi Hill did not completely lie about his discovery, he did embellish the results.

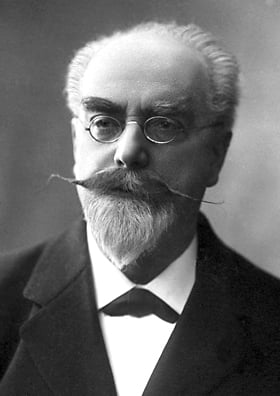

The Use of Interference by Gabriel Lippmann

In 1886, physicist and inventor Gabriel Lippmann used his knowledge of physics to create what we can consider the first color photograph without the aid of any pigments or dyes. Lippmann tapped into a phenomenon known as interference, which has to do with the propagation of waves.

By 1906, Lippmann had presented his process along with color images of a parrot, a bowl of oranges, a group of flags, and a stained glass window. The discovery won him the Nobel Prize in Physics.

One might think that the story of color photography stops with Lippmann’s usage of the complex interference phenomenon, but there were problems, and we are just getting started. Mainly, as you might guess, the process itself was too complex; it required fine-grained high-resolution emulsions that needed longer exposure times, it had trouble with the broader bands of wavelength colors created by reflections, and the process required the use of toxic mercury.

When Was Color Photography Invented?

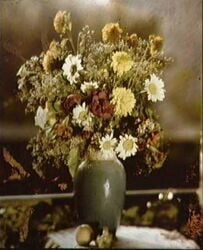

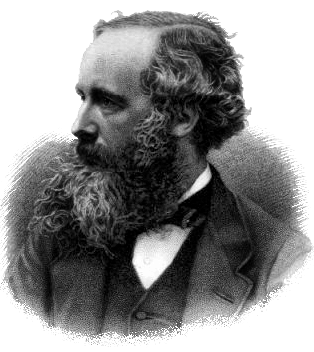

While there were multiple inventors working on multiple methods to create color photographs in the 1800s, the first color photograph is generally considered to be unveiled by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1861.

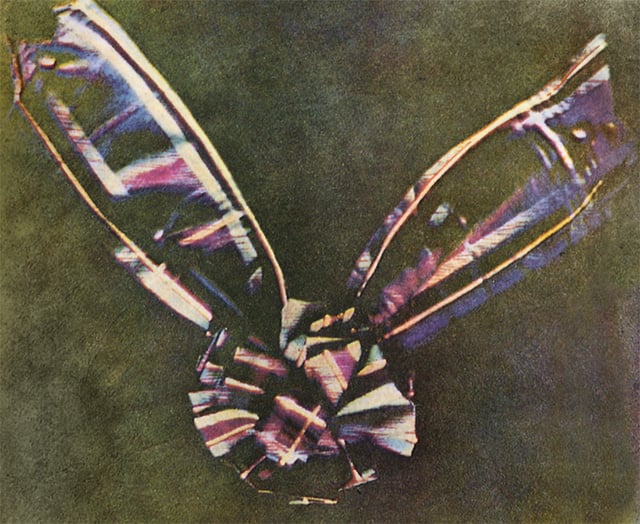

Over two decades before Lippman was developing his interference technique for color photos, Maxwell was hard at work and ready to define a new color theory that dictates the foundation of how we reproduce colors to this very day. Maxwell proposed the idea of taking photographs of a scene through red, green, and blue filters. Once the images were played back on projectors with matching filters, they would overlap to create a complete color image. Maxwell presented how the principle could then be applied to photography in 1861 during a lecture at the Royal Institution with his famous photograph of a tricolor ribbon.

Maxwell’s photo was the first durable color photographic image.

Oddly, Maxwell’s method was pushed into the background while others, such as Lippmann, presented their results. However, by the late 1890s his work was being reexamined.

A German scientist named Hermann Wilhelm Vogel discovered that he could use the three-color theory and create emulsions only sensitive to particular colors by adding specific dyes. However, it took time for the process to ultimately work itself out. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that the emulsions were accurate and sensitive enough for traditional photography.

Color Photography Gets Increasingly Easier

Needing to take the same photograph three different times with three different filters was troublesome — the camera could be accidentally moved, or the scene itself could change. As a result, two types of color cameras were released to assist photographers in their color photography endeavors.

The first style of camera used a lens that could separate the incoming light through three different filters and thus take three photographs at the same time. The second style of camera introduced still exposed images one at a time but featured a drop back that allowed photographers to quickly swap out filters and emulsion types. The process was still not easy, but by the 1910s photographers were able to be out in the field capturing color.

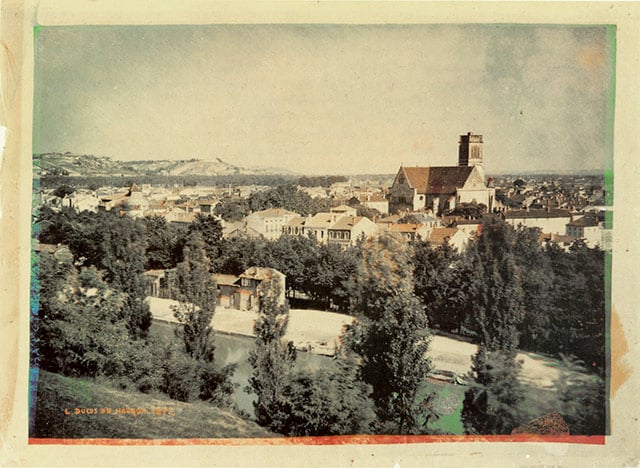

Louis Ducos du Hauron felt he had a better idea for the process: to lay three different color recording emulsions on top of each other so that the process could be exposed at once in any ordinary camera system. Blue was placed on top of the three-emulsion ‘sandwich’ with a blue blocking filter behind it because blue light affects all silver halide emulsions. Behind the blue filter blocker sat the green- and red-sensitive layers. Hauron’s idea was an important step forward for the industry. One setback, however, was that each layer tended to soften light as it passed through to the emulsion.

Although not a perfect solution, the “tripacks” were sold to consumers. In the early 1930s, American company Agfa-Ansco produced what they called “Colorol”: a roll-type film for snapshot cameras. The average consumer could now purchase film for their cameras and send the negatives back to Agfa-Ansco for development. The images were not the sharpest due to the light becoming diffused in the layers but were enough for the non-professional.

Kodak Takes Color Photography Mainstream

Of course, the hero to arrive and revolutionize color photography was Kodak. In 1935, Kodak introduced their first ‘tripack’ film and labeled it as Kodachrome. Oddly enough, the development was thanks to two musicians, Leopold Mannes and Leopold Godowsky, Jr., who began experimenting with the color process. The duo was eventually hired by Kodak Research Laboratories and, as a result, created one of the most beloved films to this day.

The refined Kodak coloring process used three layers of emulsion on a single base that captured the red, green, and blue wavelengths. The processing of the film was quite involved, but Kodak kept with their motto of “you press the button, we do the rest” and simply had their customers mail back their finished rolls for prints/slides. Eventually, in 1936, Agfa was able to refine Kodak’s development process by developing all three layers at one time.

Beginning in the 1960s, Kodak’s Kodachrome, along with other film brands, had begun to establish a presence in the market, but they were still much more expensive than standard black and white film. By the 1970s, prices were able to decrease enough to make color photography accessible to the masses. And finally, by the 1980s, black and white film was no longer the dominant medium used for daily snapshots of life.

Today, to the disappointment of many film enthusiasts, Kodachrome is no longer being produced as the last roll of film came off the production line in 2010. And of course, for the rest of us shooting digital, we have quietly closed the door of color film photography and moved on to digital sensors.

Just remember, the next time you pick up your digital camera, to thank Maxwell for his RGB color theory and the developments in color photography that have followed to this day.