The First Photo: Nicéphore Niépce’s ‘View from the Window at Le Gras’

It has been over half a century since Swiss photo historian Helmut Gernsheim donated the world’s earliest permanent photograph* to the University of Texas for public display in 1963. This article is a look at the story behind Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras, the world’s oldest known photograph captured with a camera.

Like what I felt at Jamestown, Virginia, when I stood on the northern bank at a twist in the James River, closed my eyes, smelled the brackish water, and transported myself back to 1607 when a small band of native inhabitants watched in awe as the first permanent English settlers arrived in the New World in their tall-masted ships.

Or when I saw the actual Wright Brothers “flyer” from 1903 on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and then visited Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, where the brothers flew it a few hundred feet over the sand dunes.

Maybe it’s not up there with settling a continent or inventing a new mode of travel, but I had the same amazed feeling when I looked at the world’s oldest photograph* in a display case in Austin, Texas. Let me tell you how I came to be standing there at the Harry Ransom Center on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin, staring at the world’s first photograph created by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, the world’s first photographer.

The French Connection

Many people credit Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre with being the “father of photography.” While he may have been the first to make it practical with his Daguerreotypes – those gorgeous little polished copper (silvered) plates that show such amazing detail – it was really his ill-fated partner, Nicéphore Niépce, who was the world’s first photographer.

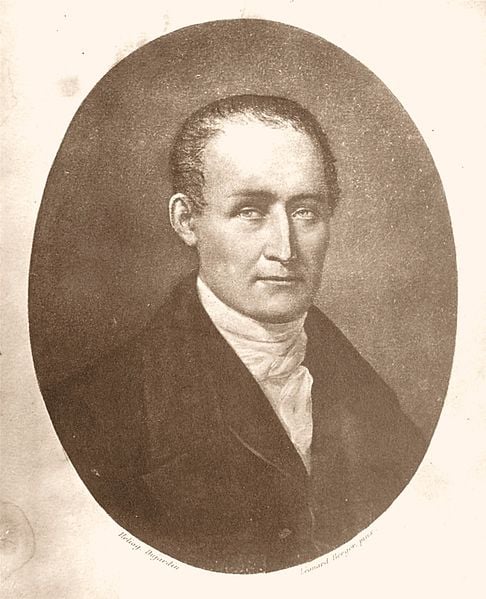

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce was what is sometimes called a “gentleman scientist.” In the early 19th century this wasn’t uncommon — middle-aged men (mostly) who were financially independent, who had time on their hands, and who had a single-minded curiosity about the world around them. They were the amateur tinkerers and inventors who brought us many important discoveries: Michael Faraday (the generator), Gregor Mendel (genetics), and even Charles Darwin.

Niépce, along with his brother older brother Claude, were busy inventors and tinkerers, collaborating on projects together. After their military service, they began work on the ingenious Pyréolophore, considered the world’s first internal-combustion engine and for which they received a patent in 1807. The brothers would spend the next 20 years — and most of their family fortune — on improving and trying to commercialize the Pyréolophore. But Nicéphore Niépce also kept up an interest in trying to use light to reproduce images, especially when combined with a camera obscura (box camera of the time), and he began his experiments in earnest around 1816 while his brother was preoccupied with the Pyréolophore.

Burgundy

When I was preparing to travel to the Arles Photo Festival in southern France on a consulting trip one year, I thought: Why not find out more about the history of photography? I would be in France anyway, so why not go whole hog and see where it all started? I planned some extra days at the end of the trip so I could find ground zero.

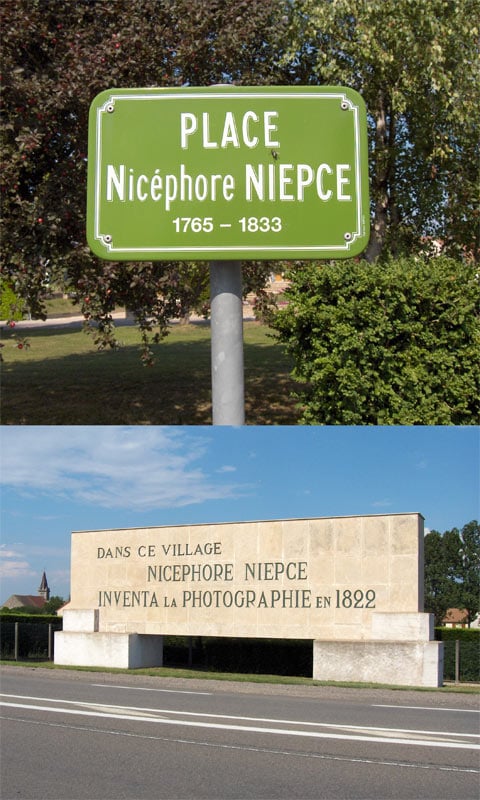

If you travel due north from Arles on the main roads, you eventually enter the region of Burgundy, best known for its wine. And in the southeast corner straddling the river Saône is the town of Chalon-sur-Saône (current population 48,000) where Nicéphore Niépce was born and lived most of his life. He is one of the “notable people” associated with the town (the other was a double agent in World War II) and the small village, Saint-Loup-de-Varenne, where he had his country house and workshop. You can’t really miss Niepce’s presence here with a museum, several parks, plaques, and statues commemorating him.

After visiting the Niépce Museum in Chalon (Musée Nicéphore Niépce), I saw the house where he was born, but I wanted to see where it all happened, which was not in the town but at Le Gras, his family estate just six kilometers away in the village of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes (population 1,000).

Where It All Happened

In 1999, the French photography school SPEOS became a tenant of the private residence of Niepce’s Le Gras estate when the school’s founder, photographer Pierre-Yves Mahé, rented the part of the house that was used by Niepce as his laboratory-workshop. With Jean-Louis Marignier, a scientist at the French National Center of Scientific Research, they restored and recreated Niepce’s working conditions and rediscovered the site of his photo experiments.

I arrived at Le Gras on a hot sunny day in summer. After meeting up with my private guide (Aurélie) at the nearby Le Bistro (café/museum shop), we went to visit the house.

The large house, part of which is now a museum, sits at the end of a quiet, gravelly road that soon crosses a railroad track. We ducked into the small front doorway, walked up the narrow stairs to the second floor (first floor in France), and into the first of two main rooms. This room had copies of his small camera obscuras as well as image reproductions. But I was headed for the second room.

I stood at the entrance of “the room” and took it all in. It was a pleasant space with two large windows on each side of a fireplace. There were two tables displaying various chemicals and implements that Niépce had used in his many experiments, and at the far side stood a large camera obscura raised high on a pedestal and pointing out the far window. This camera is an exact copy of the actual one used by Niépce that sits in the Niépce Museum in Chalon.

I walked slowly to the camera, turned to the open window, and there I saw it with my own eyes: “Le Point de View de la Fenêtre du Gras” (in English: The View from the Window at Le Gras). I was looking at the actual courtyard view.

Sort of. A few things had changed. First of all, most of the buildings and objects in the photo have long since disappeared. That’s to be expected after 187 years and multiple homeowners. And the window itself, as it turns out, had been moved 70 centimeters to the left to make way for a fireplace and chimney. But these are minor points, right? I mean, here I was standing on the actual wide-plank floorboards (rediscovered by Mahé) that Niépce had walked on to create the earliest existing photograph in history. With a light breeze coming in through the open window, I closed my eyes, and I was there in 1826. Fantastic!

How It Happened

After a lithography craze swept France in 1813, Nicéphore Niépce began experimenting with lithographic printmaking but with a twist: he took paper or vellum engravings, varnished them to make them translucent, placed them on metal plates coated with various light-sensitive solutions of his own composition, and exposed them to sunlight, a process he termed “Heliography” (sun writing). He then acid-etched the plates, cleaned them, and used them to make final prints on paper.

During these lithography trials, he also experimented by putting light-sensitive plates at the back of a camera (camera obscura), but he was unable to prevent the images from fading, a problem that affected all early photographic experimenters. Around 1816, Niépce discovered that he produced his best results when using a solution of bitumen of Judea (asphalt), which dates back to ancient Egypt.

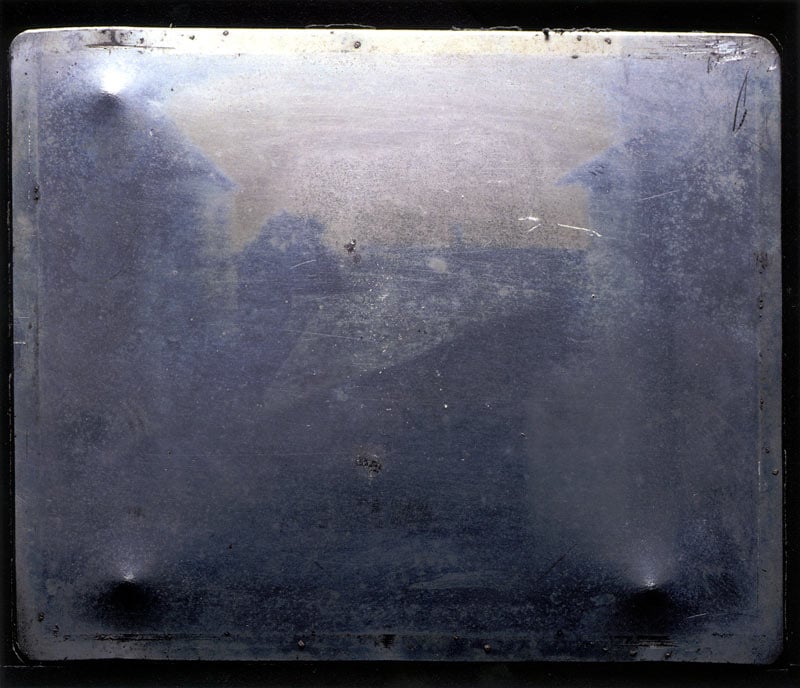

Finally, in 1826–1827 (the exact year is debated), the chemical process, the power of the camera, the successful quest for permanence, and the combined curiosity of the inventor all came together: Joseph Nicéphore Niépce made the first permanent photograph from nature with a camera. Here’s how he did it: He coated a pewter plate (pewter being an alloy of tin, copper, and lead) with the same solution from his previous experiments and placed the plate into a camera that was looking out from that upstairs window of his house at Le Gras. After an exposure of at least eight hours, the plate was washed with a mixture of oil of lavender and white petroleum, dissolving away the parts of the bitumen that had not been hardened by light. The result was a direct-positive picture where the lights were represented by bitumen and the darks by bare metal. This was the historic one-of-a-kind landscape photograph showing “The View from the Window…” The world’s oldest photograph.

If you want to know more, here is an excellent video that describes the house and how Mahé and Marignier figured out what Niépce had done and where:

Niépce’s Problems

In September 1827, Niépce traveled to England to visit his ailing brother who was promoting their struggling Pyréolophore project. But his brother died, and the Pyréolophore was abandoned, leaving Niépce basically broke.

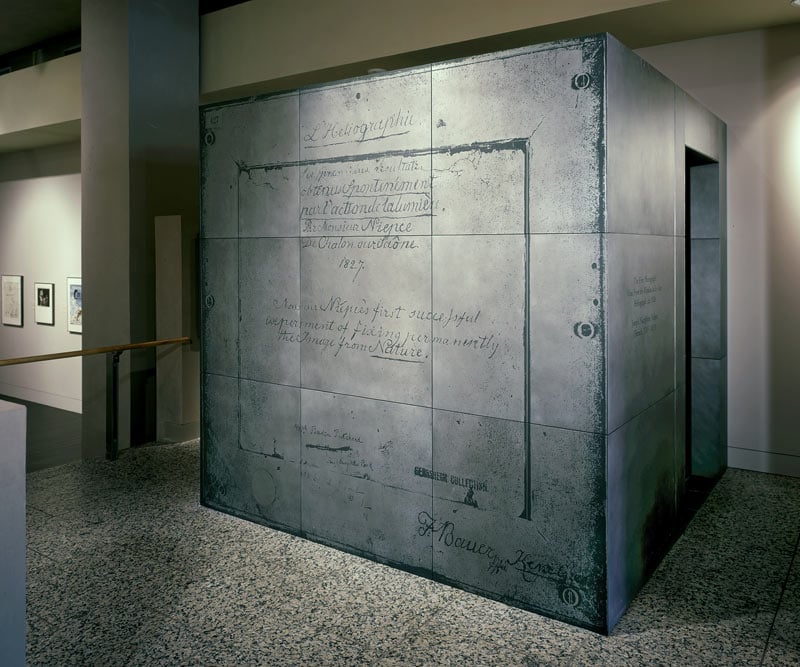

While in England, he was introduced to botanist Francis Bauer. Bauer recognized the importance of Niépce’s work and encouraged him to write a proposal for a presentation to the Royal Society in London about it. But his proposal was rejected because the secretive Niépce chose not to fully disclose his process. Niépce left for France dejected.

Upon his return to Le Gras, Niépce continued his experiments. In 1829, he agreed to a 10-year partnership with Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. Niépce kept experimenting with Heliography, dreaming of recognition and economic success, until his unexpected death from a stroke in 1833 (he was 68). His son (Isidore) took over his father’s half of the partnership with Daguerre, but things went downhill from there with Daguerre becoming photography’s superstar and Niécephore Niépce gradually fading into obscurity. Until 1952.

Now I just needed to head back to the States to see the real artifact, which turned out to be much closer to home than I thought.

Back to School

I hadn’t been back to the University of Texas campus in years (I got my undergraduate degree there). I had called ahead and arranged to meet with Roy Flukinger, who is a senior research curator at the Harry Ransom Center, which has a mission to advance the study of the arts and humanities, and which sits right on campus and within spitting distance of the iconic UT Tower (scene of the horrific shooting spree by Charles Whitman, which dramatically preceded my enrollment at the university by one month).

So what happened to the famous Niépce plate after his death, and how did it travel from Burgundy, France to Austin, Texas? Here’s the story…

After Niépce’s rejection by the Royal Society in England in 1827, he left a handwritten memoir and several of his heliograph specimens (including the “First Photograph”) with Francis Bauer, who labeled them and set them aside.

For the balance of the 1800s, the First Photograph passed from Bauer’s estate through a variety of hands, and after its last public exhibition in 1905, it dropped out of sight. Then, almost 50 years later (in 1952), photo historian and collector Helmut Gernsheim was contacted by the widow of a Gibbon Pritchard; she had found the Niépce plate in her husband’s estate after his death. Gernsheim verified the First Photograph’s authenticity and obtained it for his vast photo collection. Through Gernsheim’s scholarship and detective work, his rediscovery returned Niépce to his rightful place as the inventor of photography.

When Harry Ransom purchased the Gernsheim collection for The University of Texas at Austin in 1963, Helmut Gernsheim subsequently donated the Niépce heliograph to the institution. This is what I wanted to see in the flesh.

Roy greeted me in his office where we discussed my trip to France. He had not been to the Niépce house yet so he was curious about what I had seen. Then he led me down to the ground floor to view the plate. With the help of scientists at the Los-Angeles-based Getty Conservation Institute, they had designed and built a special room for it with an environmentally controlled, glass-walled case filled with inert gas and continuously monitored by both the Center and the Getty.

The small room (see image below) has two openings (for entry and exit), and Roy hung back so I could be in the room alone.

I was finally here, looking at the object of my quest: the Niépce plate. Oh my god, I thought, taking a breath: this is THE first photo. The actual one. Not a reproduction but the original. Right in front of me.

Housed in its original Empire-style gold frame, the photograph itself seemed small (it’s only 16×20 cm or 6.3×7.9 inches), but what struck me hardest was the fact that I couldn’t see the image! I found myself just staring at a piece of polished metal. But remembering what Roy and others had said, I started maneuvering myself away from perpendicular and started seeing glimpses of the image as I moved. I ended up leaning and squatting every which way in trying to make the image out, which I finally did. I couldn’t get a much better view than you see in the full-front image below, but I can verify that the image is there. I asked Roy if the difficulty in seeing the image was in any way a result of fading or environmental deterioration, and he just laughed. “No way,” he said. “The details are faint, it’s true, due not to fading but to Niépce’s underexposure of the plate.” Interesting to think of an 8-hour exposure as being underexposed!

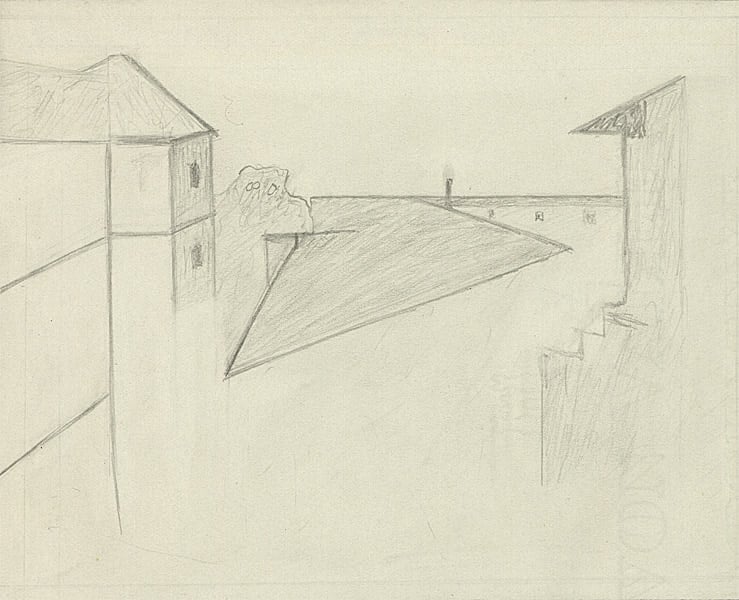

To help the curious reader make out what they’re seeing (or not seeing) in this latest reproduction of the actual Niépce plate above, here’s a sketch (below) made by Helmut Gernsheim with the key elements showing. From left to right: the pigeon-house (upper loft of the house), a pear tree, the slant-roofed barn, the bakehouse with chimney, and at far right, another wing of the house. As already stated, most of these elements are no longer there.

What’s really interesting (and a bit puzzling at first) when viewing a reproduction of this image (seen better at the top of this article) is that there appear to be shadows on both sides of the courtyard. Possible? You bet, if you’re making an 8-hour exposure and the sun is moving across the sky all that time. Try it and see!

Mission Accomplished

While the invention of photography may not rank up there with electricity or manned flight, it has had, as we all know, profound effects on this world and its people. The ability to capture a view of the world (or as Niépce himself wrote in 1828: “…to copy nature with the greatest fidelity”), to hold it, to share it… is such an important part of our lives now, but remember that it was only a dream a mere 200 years ago. A dream of a few, like Joseph Niécephore Niépce, and now practiced by millions. Progress in art and science always owes big debts to those who have come before, and I feel lucky to have experienced first-hand the photo that is the cornerstone of the process of photography, which has so revolutionized our world.

Places to Visit

Harry Ransom Center: University of Texas at Austin

First Photograph on permanent display. Admission free.

Musée Nicéphore Niépce (Chalon-sur-Saône)

Open every day except Tuesdays and holidays. Admission free.

* The Harry Ransom Center carefully describes the First Photograph as “the first permanent photograph from nature.” SPEOS calls it: “the earliest existing photograph in history.” The author calls it simply: “the world’s oldest photograph.”

About the author: Harald Johnson has been immersed in the worlds of photography, art, and publishing for more than 30 years. A former professional photographer, designer, publisher, and art/creative director, Harald is the author of the groundbreaking book series “Mastering Digital Printing,” an imaging/marketing consultant, and the founder of the photo competition site PhoozL.