The Decisive Moment: What Henri Cartier-Bresson Actually Meant

![]()

The photographic master Henri Cartier-Bresson made some key observations about photography, translated as “the decisive moment” which is often (incorrectly) characterized as: “capturing an event that is ephemeral and spontaneous, where the image represents the essence of the event itself.”

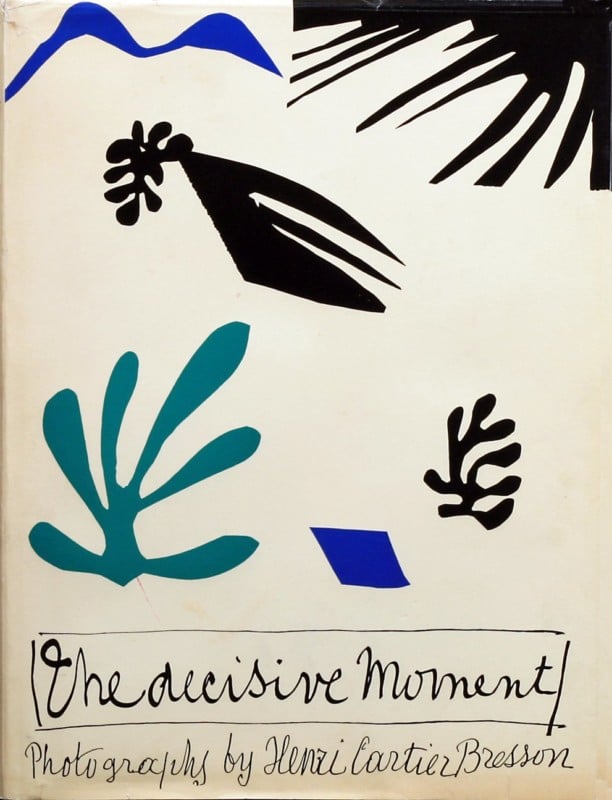

The book Cartier-Bresson penned in 1952, in French, was called Images à la Sauvette (“Images on the Run”) and along with a great portfolio of his work, is a very concise review of his process of photojournalism. It was quite literally about taking pictures in a dynamic and moving world. He used the term “decisive moment” in his writing, with very specific meaning, but the term was appropriated as the title in the English translation and has led to a generation that misses the point entirely.

Note: All quotations are from Cartier-Bresson’s “The Decisive Moment” Simon and Schuster/Editions Verve, 1952.

The Decisive Moment is Only About Composition

Here the decisive moment is described:

If a photograph is to communicate its subject in all its intensity, the relationship of form must be rigorously established. Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality… In a photograph, composition is the result of a simultaneous coalition, the organic coordination of elements seen by the eye. One does not add composition as though it were an afterthought superimposed on the basic subject material, since it is impossible to separate content from form.

Composition must have its own inevitability about it.

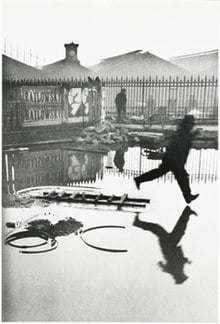

But inside movement there is one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance. Photography must seize upon this moment and hold immobile the equilibrium of it. [emphasis mine]

The decisive moment is a property of vantage point and framing (and of course timing), and not about the quintessence of the external event. His point is that in the swirl of humanity and nature, all around us, there are occasional fleeting moments where moving objects align naturally in the frame.

It is true, however, that when all those compositional elements align, the thing that you’re photographing can reveal something magical and iconic. But this is a result of the composition. And capturing it really cannot be accomplished through organized thinking and forced structure— it happens through instinct, of pressing the shutter release at an instant based on intuition.

Composition must be one of our constant preoccupations, but at the moment of shooting it can stem only from our intuition, for we are out to capture the fugitive moment, and all the interrelationships involved are on the move.

I find that this demonstration of physics is a good illustration of how moving objects in the real world can seem chaotic and random, but periodically, in certain moments, there is pattern and harmony, which quickly dissipates (You might want to mute the sound on this video):

The real world obviously isn’t this structured, but these feelings underly catching “decisive moments” — the instances when objects in motion achieve visual harmony.

In addition, because of this position, Cartier-Bresson makes a case against cropping — pointing out that if you compose carefully in shooting, cropping won’t create balances and harmony that you missed. One can debate that many great and famous photos are the result of cropping — the portrait of Stravinsky by Arnold Newman is one example of many — but Cartier-Bresson’s desire to accomplish this in-camera is laudable (and also a dig at magazine editors who might crop a “good” photo — which usually kills it):

If you start cutting or cropping a good photograph, it means death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions. Besides, it very rarely happens that a photograph which was feebly composed can be saved by reconstruction of its composition under the darkroom’s enlarger; the integrity of vision is no longer there.

He Disses The Rule of Thirds, Golden Mean, and Other Rules

Importantly, Cartier-Bresson articulates why “rules” are not the way composition is done. And while the Golden Mean (and I would add, The Rule of Thirds) might be interesting for analysis they have no place in taking a photo:

Any geometrical analysis, any reducing of the picture to a schema, can be done only (because of its very nature) after the photograph has been taken, developed, and printed — and then it can be used only for a postmortem examination of the picture. I hope we will never see the day when photo shops sell little schema grills to clamp onto our viewfinders; and the Golden Rule will never be found etched on our ground glass. [emphasis mine]

I think Cartier-Bresson would be bummed by the use of the Rule of Thirds grids that are sometimes provided in camera viewfinders, and utterly inappropriate as foundations for teaching photographic composition.

A Dynamic Situation in a Single Image

Early in the book, he articulates his ambition to capture the essence of a dynamic situation in a single image — the source of the misuse of “a decisive moment” —

I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life — to preserve life in the act of living. Above all, I craved to seize, in the confines of one single photograph, the whole essence of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.

He continues to describe a photo “story” — a series of photos used to cover an event. This is often conflated with the above ambition. But he’s suggesting that it would be unusual for a single image to convey what a series of images can.

Sometimes there is one unique picture whose composition possesses such vigor and richness, and whose content so radiates outward from it, that this single picture is a whole story in itself. But this rarely happens.

Not Over (or Under) Shooting

He warns about overshooting; photographers need to balance shooting a ton of photos and not shooting enough and missing something important. A photographer needs to be discriminating.

“[The real world] offer[s] such an abundance of material that a photographer must guard against the temptation of trying to do everything…” Cartier-Bresson writes. “It’s essential to avoid shooting like a machine-gunner and burdening yourself with useless recordings…”

This is particularly apt today, with the low friction in shooting, and shifting the burden to exhaustive post-production. Of course you don’t want to miss the moment, and certainly there are subjects everywhere that could be made interesting, but he suggests this coverage needs to be measured.

Candid Photography for Authenticity

Cartier-Bresson discusses the importance of being surreptitious in shooting if you want to capture something authentic. Remember that the small high-quality camera was relatively new, and so was the attraction to candid photography, of which he was a proponent. He says:

In whatever picture-story we try to do, we are bound to arrive as intruders. It is essential, therefore, to approach the subject on tiptoe — even if the subject is still-life. A velvet hand, a hawk’s eye — these we should all have.

He says that if your intention to shoot is made obvious, you need to back off and get your subjects comfortable with your presence. “When the subject is in any way uneasy, the personality goes away where the camera can’t reach it.”

Related, he argues for shooting in natural light, so as not to disturb the true scene. “And no photographs taken with the aid of flashlight either, if only out of respect of the actual light — even when there isn’t any of it. Unless a photographer observes such conditions as these, he may become an intolerably aggressive character.”

On Finding Subject Matter

Cartier-Bresson makes the case that many others have made — that there is no end of possible subject matter (and as Elliott Erwitt said years later, that photography is less about the object and more about how you see it.)

Cartier-Bresson says “There is subject in all that takes place in the world…” and “In photography, the smallest thing can be a great subject.” He continues “Subject does not consist of a collection of facts…” which speaks to the distinction between photographing objects vs. moments. “There are thousands of ways to distill the essence of something that captivates us.”

He goes on to detail shooting portraits and faces, and in attempting to capture the identity of the sitter, noting the problematic relationship with a client who wants “to be flattered, and the result is no longer real.”

The Decisive Moment is considered one of the most important books in the 20th century about photography, and there are ample lessons in his elegant text, illustrated by his historic work. But the continued misuse and misunderstanding of his lessons should be revisited by photographic instructors.

P.S. If you enjoy this perspective, I encourage you to take one of my workshops through the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops. There are 3-week online programs throughout the year, and this August there is a special in-person 1-week intensive that should be fun for any creative amateur, maybe if you’ve plateaued, feel like you’re good at picture taking, but want to push yourself. Anyway, Thanks for listening.

About the author: Michael Rubin, formerly of Lucasfilm, Netflix and Adobe, is a photographer and host of the podcast “Everyday Photography, Every Day.” The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. To see more from Rubin, visit Neomodern or give him a follow on Instagram. This article was also published here.