Color Filters for Black-and-White Photography: A Complete Guide

![]()

Lens filters are one of the most affordable yet also most versatile accessories you can stow in your lens bag. Some of them, like polarizers and UV filters, are practically ubiquitous in modern-day photography, used both to lend images a unique look as well as to protect your costly gear.

Today, let’s rectify that. By analyzing not just what color filters are and how they work, but what has affected their greatly changing popularity over the years, it’s easy to determine how color filters may fit into your creative process, too!

Table of Contents

Identifying a Color Filter

Hold a color filter in your hand, and two things are likely to stick out to the naked eye right away. The first is the intensity and clarity of the solid color it radiates. Punchy, strong contrasts that are very aesthetically pleasing are the hallmark of a high-quality color filter.

The second is the physical similarity between color filters and any of the other lens filters you might already be familiar with. Color filters use the same filter threads and the same construction as any other lens-mounted, circular filter.

The only difference is the way the glass surface is treated to achieve the desired effect, making the learning curve for those experienced in using filters practically zero.

What are Color Filters Used For?

This raises the question: why should you use color filters?

The answer is a bit complex (I would not have written a whole guide about it if it wasn’t), but in a nutshell, color filters are there to help you control contrasts and light balance in monochrome photography.

If applied to color photography, the color filter will do something very simple indeed: shooting with a red filter will paint your whole frame red, shooting with a green filter will make everything in your viewfinder appear green, and so on.

But it is in monochrome photography that color filters can really do something unique and interesting.

How Color Filters Work

When shooting through a color filter, certain wavelengths of light are prevented from reaching your film (or digital sensor, for that matter). On a red filter, this would correspond to all wavelengths of light except those that appear red to the naked eye. Likewise, a green filter removes as much as possible except for the visible green spectrum, and so on and so forth.

Or, to put it another way, which might be more intuitive for some: the color of the filter that you can see with the naked eye while looking right through it is the part of the spectrum of light that passes through to your exposure. In monochrome photography terms, that means that that color will come out lighter than usual. In real-life use, few color filters are so perfectly made that they will only reflect the visible light corresponding to their intended color. Hence, a red filter might also exclude some parts of the spectrum bleeding into magenta or orange, just in less noticeable amounts.

Also note that color filters are as much defined by what colors they transmit as by the ones they exclude from transmission. For a yellow filter for example, the most heavily blocked wavelength of light is blue, the complementary color of yellow. This is why bright blue skies can come out looking very dark when shooting with a yellow filter!

The Whole Palette of Color Filters Available Today

Let us take a closer look at each of the color filters for black-and-white photography commonly employed today, and how their effects translate to the final image.

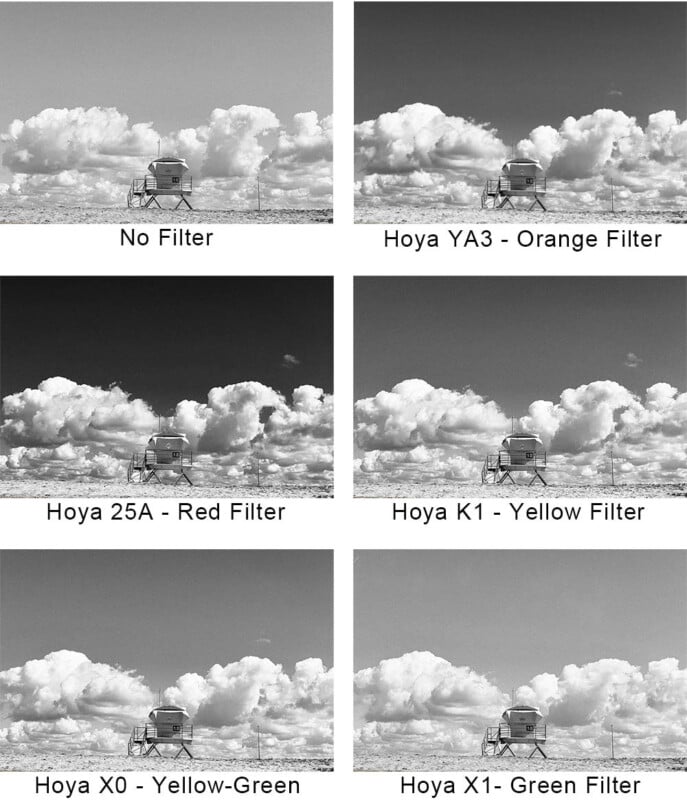

Yellow Filters

The yellow filter is by far the most common color filter in monochromatic photography. In fact, it has been considered the standard filter to use since the early days of the medium, and most young photographers were trained during the last century to keep a yellow filter on their lenses by default.

Why is that? In simple words, it’s because the yellow filter affects your image in subtle ways that are more often welcomed than not, making it fairly universal.

Yellow cuts through small mist or fog relatively easily, clearing up the frame a little. It also increases the contrast between clouds and the sky, helping prevent that overblown “whiteout” look that you can get on a bright day.

Furthermore, many people find medium and light skin tones look more pleasing through a yellow filter, which helps in portraiture.

![]()

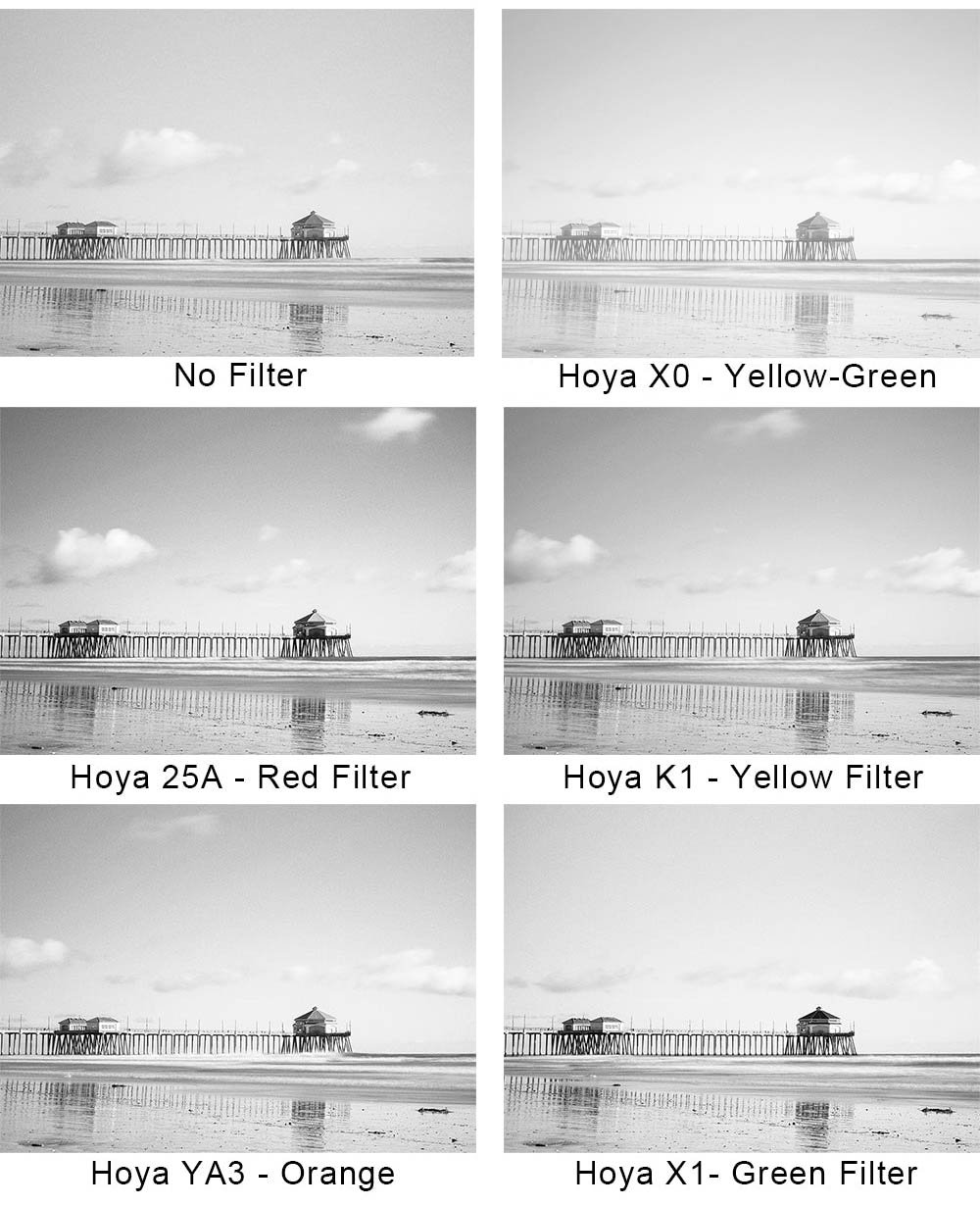

Green Filters

A landscape photographer’s perennial favorite, green cuts through the muddiness that often results from shooting wide, open areas covered in thick foliage. By filtering out large parts of the green spectrum, it allows contrasts between leaves, flowers, trees, and other natural elements to stand out more, making them more crisp and three-dimensional in appearance.

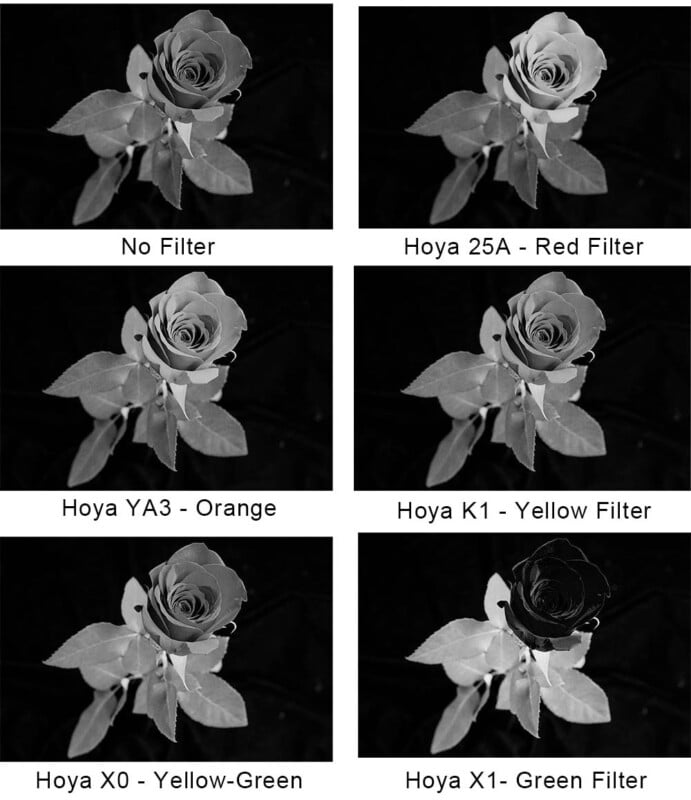

Red Filters

Red filters create a similar effect to yellow filters, though the results may look much more intense. Like yellow, filtering red separates clouds from the sky. However, red filters do more than just add a subtle layer of contrast – on a bright day, the blue sky will show in your photo as near-black while clouds stand out in punchy shades of dark gray!

Patterns, such as the texture of brick tiles in architecture or the fine details of skin, look much grittier and more detailed through a red filter. This is often employed to lend photos a “weathered”, rough look.

Also like yellow, red cuts through fog, mist, and thin cloud layers. However, it does so much more potently, allowing the red filter to eliminate almost all forms of atmospheric haze from the picture and clearing up distant scenes to a significant degree.

![]()

Orange Filters

Orange filters are neither as common as red nor as yellow, but they present a neat middle ground between the two.

Not as intense as the former but much more noticeable than the latter, they are especially useful for balancing out certain skin tones. They also render more interesting details and contrasts in light-colored organic subjects, such as flowers and other plants where a stronger green filter would darken too much of the frame.

Blue Filters

Even less common is the blue filter. This filter essentially does the opposite of the red filter – its effect is about as potent, yet instead of cutting through fog and sharpening textures, it appears to smooth out color gradients and bring out haze and mist more.

While rare, blue filters can be useful if you are dealing with an overblown scene and you wish to bring down the contrast to let certain details stand out more.

![]()

Special-Purpose Colors

Beyond these “standard” color filters, there are many more options that are rarely discussed. Given enough time and diligence, you can probably manage to find at least one color filter for every named shade of the visible light spectrum!

However, that doesn’t mean that every single color filter imaginable will do something aesthetically preferable to your image.

Most rare and unusual color filters for monochrome photography will state relatively clearly on their packaging what precise use case they are intended for.

To name just one example I am familiar with, the French brand FOCA made a special brownish filter called the “DYMA” for their own cameras. Its color profile absorbs roughly the same spectrum as a yellow and green filter combined (though slightly less intensely than either), making it an ideal solution for landscape scenes heavy in flora.

Color Filter Factors

Do note that not every color filter is created equal. I am not just talking about obvious issues of quality from off-brand gear, but rather about something called the filter factor.

Every color filter will display a small factor labeled “X”, followed by a number. This is usually found on the rim of the filter, and the number indicates the factor of exposure lost.

Because color filters literally remove light from your image, you do need to adjust exposure accordingly. The filter factor helps you determine the amount of extra light you need to push through your lens to achieve the same exposure as without the filter.

Note that filters with stronger effects, such as green and red, will naturally remove more light than more subtle filters and thus carry a higher filter factor.

Thankfully, most modern cameras are perfectly capable of compensating for this automatically by using TTL light metering. Still, it’s handy to know about filter factors to be able to do quick exposure estimations in your head when need be.

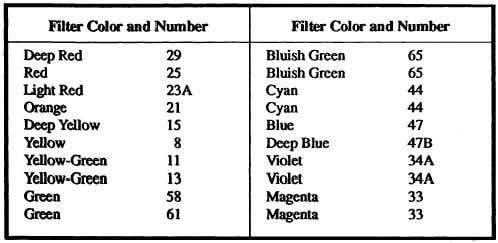

Wratten Numbers for Color Filters

There is one more way in which color filters differ from one another, even two of the same color!

That is because there is no universal standard on, for instance, the shade of green that is considered appropriate for a green filter to have.

Rather, all filters come in many different shades, or intensities, and it is up to you to choose which to use! When I mentioned yellow as the long-running standard for black-and-white photography earlier, I was referring to one specific yellow: Wratten 8, also commonly referred to as K2 in the K series of Wratten numbers designed for use with tungsten light sources.

What does 8 or K2 mean? Well, if you look them up, an 8 or K2 filter is called “Medium Yellow”. This is a standardized definition based on something called Wratten codes, or Wratten numbers.

Patented originally by Kodak for their own lens filters, Wratten numbers have become the global baseline by which all shades of color filters are still measured. Because Kodak doesn’t make the original Wratten filters anymore, it is up to third-party manufacturers to adhere to the Wratten codes – and not all do, especially low-priced brands.

But generally speaking, you can still take the original Wratten designations for color filters as a guideline to understand how different shades of the same color filter will act differently.

Should You Use Color Filters In-Camera or in Post-Processing?

While simply screwing a filter of a color of your choice to the front of your lens will allow color filtering to be done in-camera, that is nowadays but one way of compensating for color contrasts in monochrome photography.

The power of digital post-processing enables us to do much of what physical color filters do in software instead of hardware. All you have to do is jump into the suite of your choice and edit the color balance of your photograph. Usually, the program will give you a few different ways of doing this, for example via sliders, or by adjusting color curves.

Some post-processing software even comes with its own color filters built-in! Select “red”, for instance, and the program will automatically filter out exactly the parts of the spectrum that a physical red lens filter would.

This has a few clear advantages over mounting filters on the lens. Digital photo editing is mostly non-destructive – you can play with the effects of different color filters, redo and undo them, and pick the one you like most.

That is especially the case when shooting RAW files, which give you much higher editing headroom than JPEGs.

By and large, skillful use of post-processing software can very closely emulate the effects of on-lens color filters.

This isn’t actually even a modern innovation per se. Already in the film era, using color filters in the darkroom when printing could, if done properly, closely recreate the effects of lens filters without having to alter the original negative.

In the end, that makes the question of whether to use color filters in-camera or in post-processing one of user preference. Some might argue that on-lens filters provide a more reliable experience – as long as you are somewhat familiar with the factor and Wratten number of your filter, you can predict what the image is going to turn out like.

On the other hand, others might appreciate the freedom of experimenting with the countless options and endless leeway for fine-tuning that modern photo editing provides.

Image credits: Header photo from Depositphotos