Cheap Kit Lenses Are Not Weak Kids’ Lenses

![]()

Well known photographer and blogger Scott Kelby recently pointed to the 18-55mm kit lens as a reason why beginners find it difficult to take good shots — it is neither wide nor long enough to create visual impact, he wrote. I’d like to respectfully disagree.

It’s precisely because the 18-55mm kit lens is cheap and common that I relish the challenge of capturing great images with it. I just love the “You shot that with a kit lens?” wide-eyed reaction when people realize how learning to read the scene and lighting makes more difference than splurging on an expensive lens upgrade.

Don’t use a lens as a crutch

I’ve serious reservations about using a lens as a crutch. Instead of being able to work any lens by understanding its inherent characteristics, photographers may be tempted to take shortcuts by using extreme focal lengths with very strong visual signatures to compensate for the lack of ability to see the image.

This is the problem with photography today: we are flooded by visually impactful images everywhere we go. Landscapes that stretch the foreground and the sky with super wide lenses, portraits with razor thin depth of field, high dynamic range images (HDR) that impossibly captures every nuance of details from the shadows and highlights.

The downside of depending on visual impact is the death of the subtle image… and of story telling. Photographers quickly learn that HDR landscapes and shallow depth of field portraits are the flavors of the day, earning compliments on social networks with comments such as “wow… wonderful colours!” and “super bokeh on that portrait… love it!” Nobody cares if you’ve captured a great street photo with a Leica 50mm Noctilux, because everyone knows the Noct is designed for taking bokelious photos of cats with the depth of field falling off from their eyes and whiskers.

Instead of being encouraged to do one’s best with whatever one has, the novice photographer is now led to believe that buying new lenses will automatically turn in fantastic images. It is the kind of marketing spiel manufacturers will have you believe that their latest wunder product will turn you into Annie Leibovitz. If Vivian Maier had taught us anything, it is that the photographer’s eye is more important than the gear. Just look at how much she accomplished with her fixed lens Rolleiflex.

A short history of the kit lens

From the very beginning, interchangeable lens cameras were sold with a kit lens to help the user get started in taking pictures. The very first kit lens was the 50mm, for the simple reason that it provided the closest view to the human eye, and that a 50mm lens is relatively bright and most affordable to manufacture. The humble 50mm lens was sold with most cameras as a kit lens for decades until the 80s, when zoom lenses came of age.

The 80s saw the arrival of plastic bodied SLR cameras, and the growth in popularity of zoom lenses. Unlike their heavy and slow predecessors in the 70s, the zoom lenses delivered significantly better optical results by the mid-80s. Consumers loved the convenience of zoom lenses, and they quickly became the popular choice for kit lenses. Starting with 35-70mm lenses, the kit lens evolved to 28-70mm as manufacturers became more proficient at making zoom lenses.

With the advent of cropped sensors DSLRs, the 18-55mm zoom lens became the ubiquitous kit lens adorning most consumer DSLRs. The lightweight and affordable kit lenses are frequently maligned for their cheap construction, and many photographers assumed the 18-55mm kit lenses to turn in mediocre optical performance befitting their kit lens status. But they couldn’t be more wrong…

Kit lenses perform better than they look

With computer-aided design (CAD), optical engineers are able to push the boundaries of lens design, churning out impressive optics even for kit lenses. Digital cameras also perform corrections for lens distortions, vignetting and aberrations, allowing even mediocre lens designs to turn in impressive images.

All the photos in this article have been shot with the Canon EF-S 18-55mm or the Fuji XF 18-55mm, and I don’t think anybody can tell me that these are blurry or fuzzy in any way. The truth is – many of the 18-55mm lenses are much better than most photographers give them credit for, provided they bothered looking past their cheap construction.

These kit lenses are small, light and convenient. And they turn in very decent performance with just a little effort on your end. Granted they have a modest maximum aperture range, but that’s what the uber-high ISO performance on your latest camera is for anyway right? They may not be suitable for specialized applications such as sports photography, but you’d be surprised what you can squeeze out of them for many genre of photography, including portraiture and macro. A 100mm macro lens or 85mm f/1.2 lens is a nice thing to have, but knowing you captured a great shot on a kit lens is something else!

Kit lenses force you to think harder

The legendary American landscape photographer Ansel Adams said, “There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept”. In today’s world where so many photographers are focused on MTF charts and pixel peeping, his words have never rung more true. Instead of thinking about how to create interesting photos, photographers focus on (forgive the pun) lenses that are sharper, faster and wider than ever.

But because kit lenses have such humble origins, photographers seldom bother to nit-pick on their optical performance, since expectations are low to begin with. You can try as hard as you want, but it will never deliver the bokeh of the more expensive primes or zooms. And with its relatively normal and limited focal range, it will never squeeze the entire universe into one ultra-wide shot, nor capture an image of a weasel riding on a kingfisher in flight.

In other words, if you want great images from the kit lens, you’ve got to try much harder than others. And if you succeed, you know you are good.

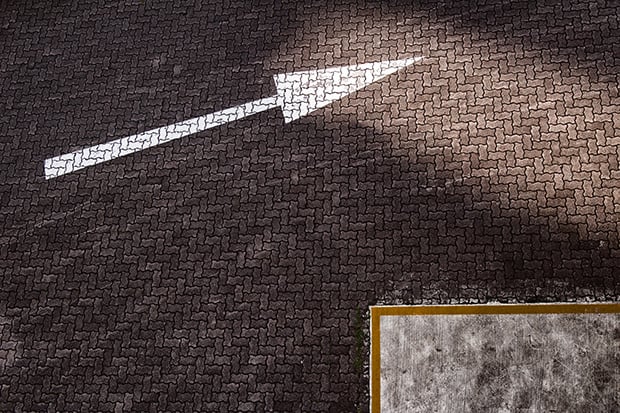

The 18-55mm kit lens forces you to see photographic opportunities, instead of chasing after visual impact with shallow depth of field or converging perspectives. You start looking harder and thinking more intensely with the limitations of the kit lens, and that helps your development as a photographer far more than buying another lens. You cannot mask your inadequacies with visual effects, and you have to probe harder to find something interesting to say about the scene in front of you. And when you do, the gratification is immense.

As you work with the 18-55mm kit lens, you become more attuned to its strengths and weaknesses, and you become more proficient in spotting images. This skill is invaluable to any photographer, and especially when you acquire many more lenses later in your journey, it will help you visualize the image way before you reach into your camera bag for the most appropriate lens. It is precisely because of the self-imposed limitation on lens choice early on, that you learn how to expand your creative eye for lens selection.

There is nothing magical about kit lenses

In fact, there’s nothing magical about any camera gear. It is what you learn to do with a specific piece of gear that allows you to create magic.

The moral of the story is that money can work for you or against you. It is true that having certain equipment does make a difference in some cases, but indiscriminate acquisition of gear can also ruin your ability to learn and see. For novice photographers, forcing yourself to shoot with the kit lens repeatedly will hone your skills to see and think critically. When it’s time to move on and purchase more lenses, you will be able to apply your trained eye to your new lenses.

I shall end with a quote by the late martial arts exponent Bruce Lee: “I fear not the man who practiced 10,000 kicks once. But I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.”

P.S. For high resolution sample photos from this article, check out this Flickr gallery.

About the author: Nelson Tan is a photographer and blogger based in Singapore. You can connect with him through his photography blog or Facebook.