How Editors Blend Art and Science to Bring NASA’s Space Photos to Life

Since it began its full scientific operations at the second Lagrange point (L2), about one million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth last year, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has enchanted people around the world. Webb’s photos have inspired many people to learn more about space and look at the night sky with unprecedented wonder and curiosity.

Thanks to OM SYSTEM for sponsoring this episode of the PetaPixel Podcast! Given the space theme, we thought it would be a great time to share a comprehensive guide to astrophotography written by OM SYSTEM Ambassador Peter Baumgarten. Learn how he plans his Milky Way photos, what he looks for in composition, the settings that he will use to capture photos of the night sky, and how he uses the rich and unique feature set of the OM-1 and OM-5 cameras to capture stunning photos of the Milky Way and Aurora Borealis.

Learn more about the incredible line of OM SYSTEM cameras and the highly respected M.Zuiko lens series by visiting explore.omsystem.com.

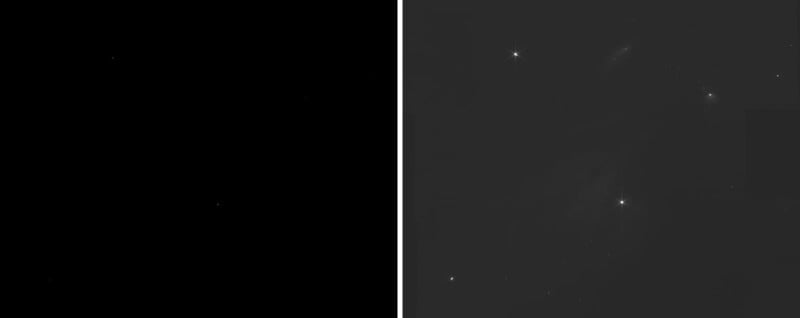

Webb’s stunning images are not beamed to Earth from the $10 billion space telescope in full color. In fact, Webb’s detectors capture monochromatic photos that are exceedingly dark.

Thanks to expert image processors Joe DePasquale and Alyssa Pagan at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, the dark gray raw images come to life in unbelievable ways.

PetaPixel spoke with DePasquale and Pagan to learn about their work, image processing techniques, the balancing act between art and science, and the critical role that visuals play in conveying scientific breakthroughs.

The Path to STScI

Joe DePasquale is the Senior Science Visuals Developer in the Office of Public Outreach at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. His work involves processing images from the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope.

Before his role at STScI, which he took on in 2017, DePasquale was the Science Imager for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. DePasquale worked there for 16 years following his undergraduate studies at Villanova University in astronomy and astrophysics.

His role at STScI is an ideal blend of his extensive scientific background and passion for art. DePasquale is an expert in fine art, photography, and music. He has even created music for some of Hubble’s outreach media, including the videos below.

Alyssa Pagan, Science Visuals Developer at STScI’s Office of Public Outreach, shares DePasquale’s passion for blending art and science. Following formal training in art and design, Pagan studied astronomy. Before finding her perfect role at STScI, Pagan worked at a bakery doing impressive cake decorating, including some fun space-themed projects.

“If you love what you do, you never work a day in your life,” Pagan tells PetaPixel, acknowledging that despite being a cliché, the adage has proven true for her at STScI.

Image Processing from the Beginning: Extracting as Much Information as Possible

Before DePasquale and Pagan create the final color images, they must first download the raw data from the James Webb Space Telescope. While they have access to some proprietary data ahead of public release, all JWST instrumental data winds up on the Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes, also known as MAST.

Webb data is downloaded as Flexible Image Transport System (FITS) files. It is an open standard digital file format commonly used in astronomy. Like a RAW image from a typical camera, people need special software to work with FITS files. Here, Pagan and DePasquale differ in their approach, with Pagan using FITS Liberator and DePasquale opting for PixInsight.

Regardless of their app of choice, they start by extending an image’s dynamic range. When someone first views raw data from Webb, the photos look dark. However, a massive amount of detail is hidden away in the shadows. With a bit of massaging, the monochromatic images burst to life, revealing distant galaxies, detailed star-forming regions, and much more.

“These instruments on Webb and Hubble have an enormous dynamic range, so when you open the images at first, they essentially look black because most of the data is contained in what we call the ‘darkness.’ It is usually a 16 or 32-bit data file, so each pixel in the image has over 65,000 possible shades of gray. That vast dynamic range can’t be accurately portrayed on a screen or even seen by our eyes, so we have to manipulate those pixel values somehow,” DePasquale says.

This process, called “stretching,” requires applying a mathematical function at the pixel level of the image. This raises the value of some of the midtones, allowing someone to see the data hidden in the darkness.

“What I like about PixInsight is that it has a tool called the screen transfer function that lets you do that transformation without actually changing the pixel values. You can work on the data, compose a color image, and do color calibration, all before you’ve done a transformation to the pixel values,” DePasquale continues, describing what is essentially a non-destructive workflow.

Like with more traditional photo editing, DePasquale and Pagan must balance detail and noise. As anyone who has shot night sky images knows, at high ISOs, it is impossible to have high sensitivity without noise, and it is very challenging to reduce noise without eliminating the finer details in an image.

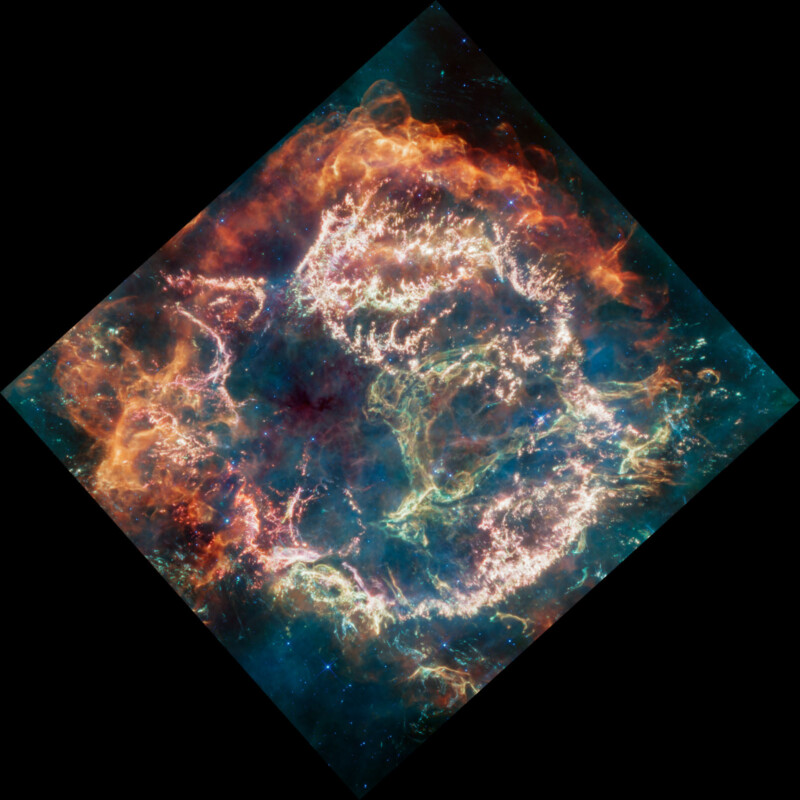

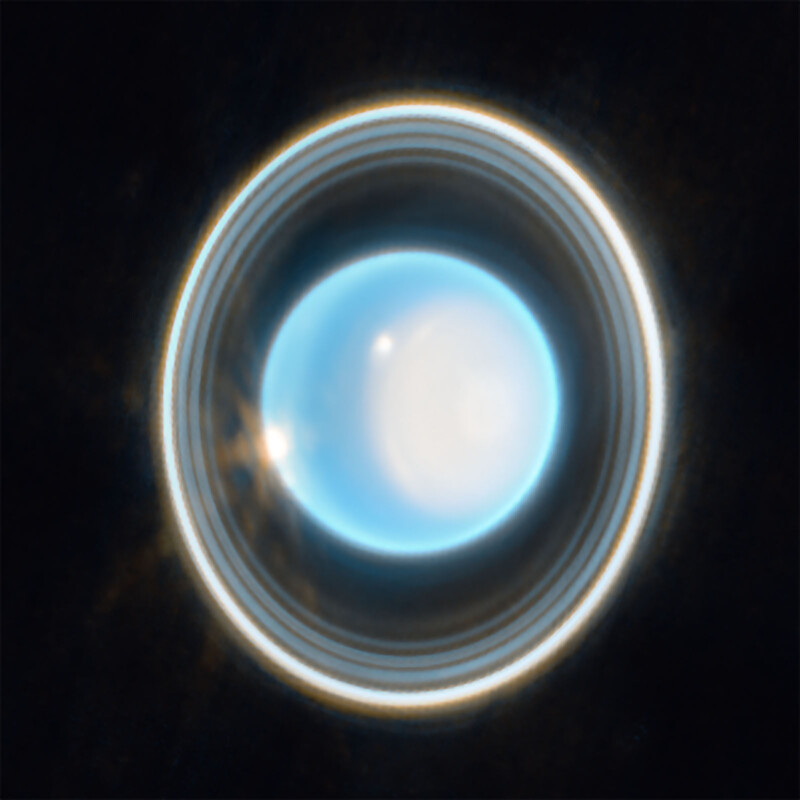

“This image combines various filters from both Webb imaging instruments, with the color red assigned to wavelengths of 4.44, 4.7, 12.8, and 18 microns (F444W, F470N, F1280W, F1800W), green to 2.1, 3.35, and 11.3 microns (F210M, F335M, F1130W), and blue to 0.9, 1.5, and 7.7 microns (F090W, F150W, F770W),” says STScI. | Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team

“It’s a bit of a balance, and it kind of depends on the object that you’re working with. But in general, the way that the limitations are, it is a balance of suppressing the noise while bringing out the faintest detail you can,” Pagan explains.

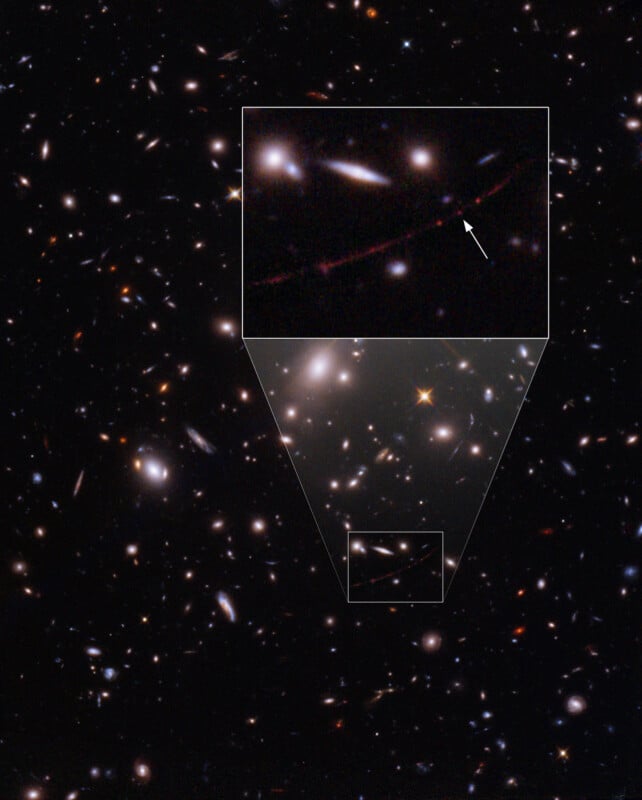

“With deep field images, you want to push that more because the science that is interesting is how far back can you see, what is the youngest galaxy you can see. But for star-forming regions, we might not push it too much because the information there is not the background galaxies,” she continues.

The First ‘Stretch’ Can Be First Sight

When Pagan and DePasquale begin stretching the data from Webb, exposing crucial details tucked away in the darkness of the raw image, they are often among the first people ever to see certain distant galaxies or other celestial objects.

“It’s always so fun, just that initial stretch, where you get to see it on your screen, it’s like ‘Whoa!'” exclaims Pagan.

“When you see those background galaxies come to life, even in images that aren’t intended to be deep field images, you recognize that you might be the first person to see this background galaxy,” Pagan says. “That just kind of blows your mind.”

“It is overwhelming sometimes. Sometimes you need to take a step back because you can forget what you’re working on, and you remember, ‘This is a Webb image, this is a very deep image that is giving us more information than we’ve ever had before.’ But even that can be hard to process,” Pagan continues.

Converting Black and White Astronomy Images to Color Blends Science and Art

For most published Webb images, multiple iterations are made behind the scenes. When working on images for scientific releases, DePasquale and Pagan work alongside scientists to ensure that the processed images accurately reflect what is interesting about the research results.

That said, it is also essential to have compelling imagery to accompany scientific releases, as it helps convey otherwise hard-to-understand scientific concepts. Often, the artistic choices DePasquale and Pagan make result in the science being easier to understand — many of these aesthetic decisions concern color.

Since Webb captures only grayscale images, some people wrongly conclude that color images from Webb — and many other telescopes, for that matter — are “false color.” This term may be accurate in an extremely limited sense, but it completely misses the mark in any practical way.

The human eye does not see in the same wavelengths of light as Webb, so no, if someone somehow made their way out to the Carina or Tarantula Nebulae, their eyes would not see what Webb sees.

However, the colors in the full-color Webb photos are rooted in rigorous science. DePasquale and Pagan have rich scientific expertise that informs their artistic decisions when processing images.

Where Does the Color Come From?

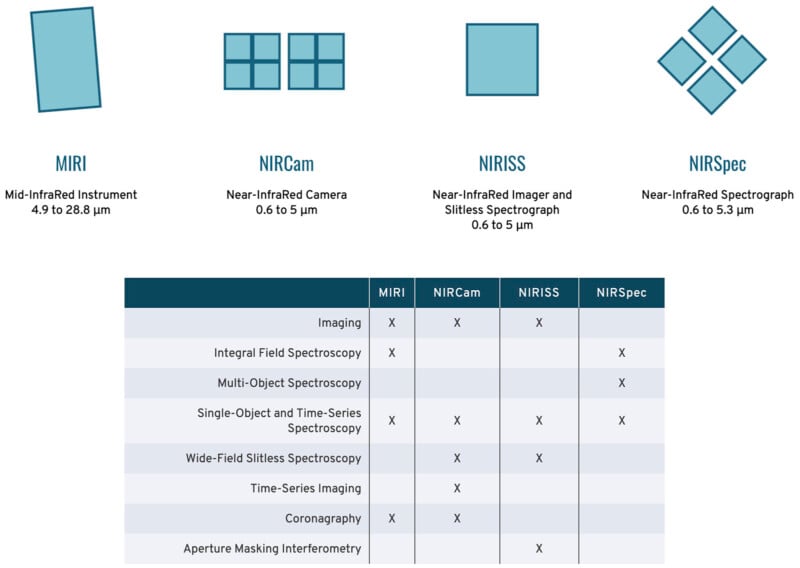

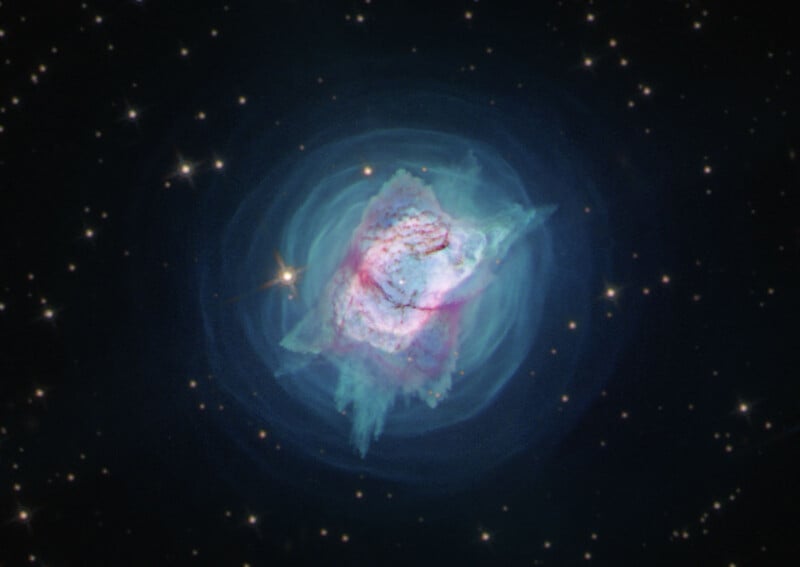

When it collects data, Webb uses a wide range of filters. The filters allow only specific narrow bands of wavelengths to pass through. Each of these filtered images, while grayscale at the start, is assigned to a particular color channel. When the colored layers are combined, the full-color composite takes shape.

Scientific image processors like DePasquale and Pagan rely upon “chromatic ordering” to apply color to Webb’s images. Going from shorter to longer wavelength filters, they apply blue, green, and red color information. Since Webb has so many filters, they may also use orange, yellow, cyan, purple, or other colors to best reflect the data Webb captures.

Pagan explains that an effectively processed image accurately illustrates the scientific importance of the underlying data while exciting the viewer.

For example, Pagan processed Webb’s Carina Nebula image seen below. Speaking about her decisions for the image, which included making the red more orange and the teal colors bluer, Pagan says, “I wanted the final image to feel organic and something that someone can connect to. These images can feel so grand, and they can make people feel very connected or very small and isolated, which you don’t want to do. You want to create a sense of context and create a parallel to what someone sees on Earth. It’s an extension of what you see on Earth. That was the choice there. And I am working with the scientists, too, making sure that an image is as true as possible.”

“We definitely want to maintain chromatic order because it’s the closest thing to how we would see it. It’s the only thing that we can sort of physically replicate in the infrared. We don’t want to break that because that might be how a predator or a bug sees in infrared. However, the filters relative to each other, or the filters in general, we might change them proportionally to each other,” she continues.

What she is getting at is that while the colors in Webb’s images may not be precisely what people would see because of biological limitations, the colors follow logically from how human vision works in the visible wavelengths.

“I will always start by chromatically ordering the data and use that as my starting point,” DePasquale affirms.

“I think that some of the more interesting images are ones where we’ve got a lot of filters to work with, so it’s not just a simple case of red, green, and blue. Cassiopeia A is a good example of that. We had more than three filters — I think it was five — and I had to figure out a way of combining them that makes sense aesthetically but also gives you the color separation you need to decipher the details in each wavelength range,” DePasquale explains.

“It doesn’t always work out. Sometimes you have reds or blues that overlap and create purple, and if you already have a channel devoted to purple, there can be color confusion,” he continues.

“There’s a balance between art and science. From the artistic side, having a clear separation of those colors and having the colors assigned in such a way that when they’re all added together, they come out to white; that’s really important for the aesthetics of an image. On the science side, colors being clear and separated enough so that you can make scientific inferences based on the colors you’re seeing, that’s where that balance comes in. There can be tension there. It may require a hue adjustment a little bit one way or the other to get separation.”

“With deep field images, I often use spiral galaxies as my white reference, and that’s really helpful. I love working with deep field images because it makes color balancing easier. Spiral galaxies contain all the populations of stars, representing all the possible colors of stars, so using it as a white reference is so helpful,” DePasquale says.

More on Noise and Artifacts

Sometimes observations, such as those for Webb’s EROs, are designed to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio. However, that is a resource and time-intensive approach. Other scientifically oriented images are done in shorter periods and are less concerned about optimizing image quality. More finesse is needed to pull out the required details and show them in the best light in the latter cases.

“I try to avoid smoothing as much as possible when working with Hubble or Webb data,” DePasquale says of visual noise. “I want to show what the detector sees. I don’t mind seeing noise in the data. I know a lot of astrophotographers go to great lengths to reduce the amount of noise in their images, to smooth them out as much as possible. In some cases, it looks like an Instagram filter has been applied to your data. I like seeing those pixels and knowing that this is what the detector saw. I’m trying to represent it in the best way possible with the available tools.”

While Pagan and DePasquale use a light hand when addressing noise in images, they also must contend with artifacts, including banding.

When using short wavelength filters, they encounter what is known as 1/f noise, also called pink noise. “It’s banding introduced by the electronics, so it’s a bunch of banding you must correct for. That’s what usually takes the most time,” Pagan says.

DePasquale mentions that they are also keeping a close eye on improvements in image processing technology, especially with the proliferation of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools. DePasquale hopes that banding might be something that AI can help clean up.

“I think this would be awesome for a neural net algorithm to figure out. In fact, last year, I was in contact with Russell Croman who has developed some great image processing tools for astronomy. One of them is called StarXTerminator, and he specifically trained it to look for Webb-type stars, that distinctive six or eight-spiked pattern, to pull those stars out. You can take an image from Webb and remove all those stars, like when trying to look at a nebula. His tools are based on neural net algorithms. I think that’s a perfect candidate for a tool that could be used for de-banding. I haven’t raised that issue with Russ yet, but I intend to at some point. I know he’s a very busy guy.”

Achieving Scientific Objectives Through Art

When photographers talk about working with RAW images inside the image editing software of their choice, the terms “photo editing” and “photo processing” are used interchangeably. However, it is crucial when discussing the work that DePasquale and Pagan do to emphasize the “processing” over the “editing.”

That said, they do work in Photoshop. As evidenced in the Photoshop files they provided to PetaPixel, they even use some of the same adjustment layers and tools that a landscape or portrait photographer might.

“It’s definitely a balancing act. The science versus the astronomy. The data versus the art. It’s a balancing act that we constantly are working with, with every image that we produce,” DePasquale explains.

“Everything in space is going to be a little exotic,” Pagan explains. “But to give people as much context as possible, I think it’s better to be, ‘This is like mountain ranges, this is like dunes, this is like the sky.’ Having those parallels is so important. Like with the Carina Nebula, that mountain region of dust is being eroded by hot stars. That’s what happens in real life when we have mountain ranges eroded by weather and water. Giving someone a sense of stability matters so they’re not just floating in the abstract.”

“So yes, it’s a little bit subjective,” she continues, pointing out that there are consistent scientifically founded pillars, like chromatic ordering, that they stick to throughout the process.

Pagan and DePasquale alike emphasize the importance of working with the data that they have. They do not introduce or eliminate data. “I’m trying to allow the data to speak for itself,” Pagan says. Working carefully with scientists to preserve the data’s integrity is paramount.

Working Closely with Scientists and Each Other

Webb’s observation schedule is jam-packed, and many astronomers and astrophysicists vie to utilize the telescope’s incredible capabilities. The STScI’s public outreach team occasionally proposes observation time to gather the data they need to create a spectacular image that appeals to the general public, but much of the work DePasquale and Pagan do is processing images for scientific news releases.

“Both Alyssa and I collaborate with the scientists who have proposed observations. We work closely with them to make sure that we’re representing the data in the best way possible, to help tell their science story and make a compelling image that draws people in and makes them excited about what the particular science topic is using that observatory’s data,” DePasquale explains.

In some cases, although scientists may have processed their images to an extent, they rarely see them look like DePasquale and Pagan’s processed files.

“When they see their data in full color for the first time, they get so excited,” Pagan says, adding that sometimes the full-color images she and DePasquale make can even help scientists see data in new ways that help inform future observations and studies. Even when people have the data, sometimes it can be instructive to see it rendered in detailed images.

The duo also works closely with each other.

“Alyssa and I have slightly different approaches, which is both interesting and good for the job that we take different paths to get to the final version of an image,” says DePasquale. “Sometimes we’ll work on images together and sort of do our own thing and bring it together and see what we produced.”

Even in cases where they must work on separate images, they maintain a strong working relationship and bounce ideas off each other. Much like the James Webb Space Telescope mission is a collaboration, so too is the image processing work at STScI.

Webb’s Early Release Observations Created an Exciting Buzz and a Huge Time Crunch

Webb celebrated its first birthday earlier this month. While the chaotic pace of the Early Release Observations (EROs) has long since slowed down to a more manageable pace, DePasquale and Pagan both look back fondly on the mad rush to prepare Webb’s first images.

“We had a pretty large team. Once we started getting data, which was on June 1, 2022, from that moment until the day that we released the images, we met every single morning. We discussed the status of the observations, how they were going, how planning was going, what data had come down, and reviewing images,” says DePasquale.

“It was just really cool to have this intensely focused period of about six weeks where we all worked really closely together to develop the program, imagery, writing, alt text, and how it was all going to be displayed. All this stuff was happening at the same time for six weeks. It’s very unusual compared to the day-to-day operations of the telescope. It was an amazing experience that I will hold onto forever,” he adds.

While it was extremely stressful and intense, Pagan also warmly recalls the early days of preparing Webb’s images. After waiting for many years for Webb to launch and begin its scientific operations and to finally see the first images, it makes sense that adversity would be more of a bonding experience than anything else.

Pagan also baked Webb-themed goodies for the team, including a cake shaped like the telescope. There are no situations that cannot be improved with baked goods.

Looking Ahead

While so much has been seen with Webb, it is only just getting started. So much more of the universe remains to be seen in unprecedented detail, and additional breakthroughs are on the horizon.

One such breakthrough could include a special kind of star. DePasquale hopes that scientists will use Webb to look at tip of the red-giant branch (TRGB) stars.

“These stars are very useful for determining accurate distances to different objects. They have a unique brightness known very well, so observing them with a telescope is like observing a 100-watt lightbulb from a distance. With a telescope, you can read that it’s 100 watts. You know exactly how bright it is and have the brightness you measured with the telescope. Using those two numbers, you can find out how far away the lightbulb is. It’s the same thing with TRGB stars,” DePasquale explains.

“In cosmology, everything hinges upon having accurate distances. It has implications for basically everything we know about the universe. Webb is uniquely suited for finding TRGB stars in other galaxies because of its ability to resolve such small-scale features of things that are far away. I haven’t seen anything recently about observations of TRGB stars with Webb, but I’m sure people will use it to make these surveys of TRGB stars to get accurate distances to different galaxies,” DePasquale continues.

DePasquale and Pagan Inspire Passion for Space and an Enthusiasm for Science Through Their Images

It is difficult to recall any scientific event that was as anticipated as the first release of Webb images. As soon as the initial pictures hit the internet, they spread quickly and were quickly seen by millions. Most people think Webb is a good investment, even in a polarized America. One reason for the overwhelming support for space science initiatives is that people get to see what results from the spending.

Before Webb’s breathtaking images reached televisions and computer screens worldwide, they were seen and processed by DePasquale and Pagan. The photos ignited instant fervor, excitement, and passion.

Some people entranced by Webb’s images will someday become scientists, astronomers, astrophysicists, and image processors. And many more people will be inspired to become more interested in science and feel more connected to the incredible sights in deep space and their neighbors here on Earth.

When asked what it feels like to work at STScI and help push the boundary of human understanding and wonder further, Pagan says it makes her feel incredibly honored and lucky.

“When I first started working here, there was a lot of imposter syndrome because I wondered why I’m the one that gets to do this when there are many talented people. At the end of the day, though, all that means is that I’m going to love what I do and spend as much time getting better at it and improving and doing the best I can. That was my promise to myself and anyone who is inspired by the Webb imagery.”

The raw monochrome data files that Webb beams back to Earth do not have anywhere near the impact that the processed, full-color images have. Many details are hidden, and the ones that aren’t are still difficult to understand for those without a scientific background. The processing work that DePasquale and Pagan do is invaluable. Alongside the incredible writers at STScI, they make science beautiful and accessible. Feeling inspired, full of wonder, and hungry for knowledge are among the greatest gifts anyone can receive, and it is a gift that Webb, with the expertise of DePasquale and Pagan, delivers to humanity in spades.

Thanks for listening to

We hope you enjoy the podcast and we look forward to hearing what you think. If you like what you hear, please support us by subscribing, liking, commenting, and reviewing! Every week, the trio go over comments on YouTube and here on PetaPixel, but if you’d like to send a message for them to hear, you can do so through SpeakPipe. This should go without saying, but please be respectful.